suit & wood

It didn’t start as an acivist act, a political statement or social or cultural reseach. To some extent it has turned into that. Not because it is what I wanted or aspired but because that is what the world wanted. I just walked. I walked for weeks, months, and people on the road asked me questions, told me their stories, gave me their opinions. They saw things in my walking I hadn’t seen myself. They hardly ever asked me if it was art. It didn’t matter. I loved that. It was so different from interacting with an audience in a traditional art space.

I sometimes questioned myself. I remember waking up one morning, on my way from Barcelona to Paris and reading a message on my iPad about the terrorist attack at the Bataclan theatre in Paris. I felt silly in my three-piece suit on the edge of the field where I had spent the night. Useless. What is the point of being on the road slowly, surviving outdoors and writing about the small events happening when the world is on fire? But when I walked on and sat down outside a bar in the next village to drink coffee and I saw people from different fields of life, with different skin colours, beliefs and customs greet each other, greeting me, a stranger, it made sense again and I took their story with me into the world.

It made sense when, already close to Paris, after some freezing nights under trees and in abandoned sheds, I knocked on the door of a hotel where the manager, after hearing my story, kindly gave me a room for a fraction of what he normally charged and I turned on the tv, tired but happy. I had taken off my muddy boots and was lying on the bed in my dirty suit that was pretty worn out after fifty walking days. On the flatscreen I saw the politicians that had just arrived in Paris by planes from all around the world lining up in their clean expensive suits for the opening of the Climate Conference, the COP21. I was on my way there. On foot. To protest in the streets of Paris. But the real protest was the walk itself. I looked at my hands. They were dirty. Honest dirt. Nothing to be ashamed of. Rather the opposite.

Every day I picked up paper trash people had thrown away in nature and on the streets. Foodwrappers. Receipts. Cigarette packages. Flyers. I folded them into small boats. I dedicated every boat to somebody who had helped me out on my walk in some way. When I arrived in Paris I was accompanied by a small fleet.

suit & walking cart

the fleet

It didn’t start like that. It started with words. Somehow it always starts with words. There is a similarity between words and steps, writing and walking. Reading a book is like going on a journey.

I read that a business suit was called a two- or three-piece walking suit once and that is still a term that is being used. There was a time when suits were considered more comfortable than what people had been wearing in the centuries before they came into fashion. Men would wear a suit for a stroll through the park. In old photos and movies you can see people wearing suits as leisure clothing. To work in. To do sports in. It is only in the last half century that the wearing of suits has become mainly reserved for formal and business activities. A capitalist symbol, connected to corporate power and money.

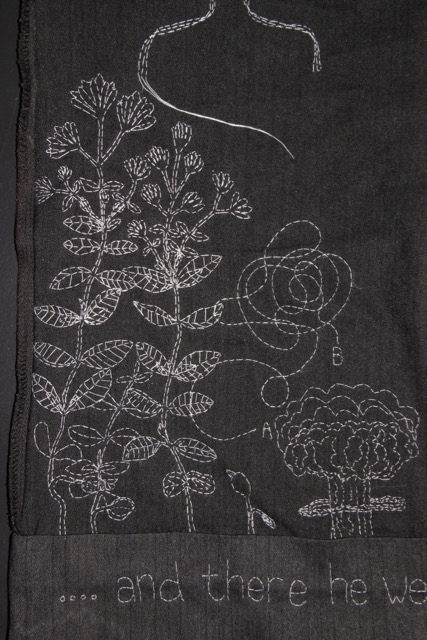

I didn’t think of that in the summer of 2012 when I bought a matching pair of trousers, waistcoat and jacket in a neutral shade of grey. I wanted to know if something called a three-piece walking suit is suitable for walking. I headed off to Belgium to walk from the west to the east of the country with a big group of artists in a walking festival called Sideways. I had been invited to join the Walking Library, carrying books through villages and fields, reading to people on the road, to fellow walking artists and to streams and forests. We walked on weekdays, in the weekend we set up the library somewhere. The suit functioned well. When it was warm, I took off my jacket and rolled up my trousers. It was handy to have many pockets. I didn’t mind stains and tears. They were traces of the journey, memories of events. I didn’t have to think about what I would wear in the morning. I had one suit and three similar white shirts. I embroidered small drawings and sometimes words on the inside of my jacket. While walking it turned into a book.

Some people would rather have wings but we don’t, we have feet. We were born to walk. Scientists say that walking gave us our brain capacity, walking turned us into the human beings we are. Walking made it possible for us to have the desire to fly and to come up with ways to turn our dreams into reality.

Walking made us fly. We can go anywhere. Still the easier it becomes to move through this world, the more disconnected we seem to get from it. We have to land again. Get close to the things. Be part of the world. Walking teaches us where we are, who we are. A slow speed makes our brain work fast. Makes us see more. Be more. And best of all: walking makes time disappear.

I made a decision on the last day in Belgium. From now on I would only walk. And so I did. Shortly after I returned home, I went on a four day walk collecting and carrying all the plastic I found on my path to create an island that would be part of the Eighth Continent, a symposium organised just over sixty-five kilometers walking from where I lived at that moment.

In the following spring I was invited to walk pilgrim trails together with two other artists, a changing group of walkers accompanied us every day. The former archbishop of Lund was among them. In jeans. I wore a suit again and inbetween the walking and talking I embroidered lines and shapes on my jacket, waistcoat and trousers, as if I captured the words of the walkers in the thread. The suit started to look like a map. I remembered an old Chinese saying that states that people who are destined to meet are connected by an invisible read thread. A thread that can be short or long, that gets entangled sometimes but never breaks.

red thread

plastic journey

It is wonderful to walk with people. But walking is very much a solitary act. Robert Louis Stevenson once wrote: “Now, to be properly enjoyed, a walking tour should be gone upon alone. If you go in a company, or even in pairs, it is no longer a walking tour in anything but name; it is something else and more in the nature of a picnic. A walking tour should be gone upon alone, because freedom is of the essence; because you should be able to stop and go on, and follow this way or that, as the freak takes you; and because you must have your own pace, and neither trot alongside a champion walker, nor mince in time with a girl. And then you must be open to all impressions and let your thoughts take colour from what you see. You should be as a pipe for any wind to play upon.”

I wondered what would happen if I would just close the door of my house behind me and walk into the world. Not in order to be alone, but to be in my own pace, to be in the rhythm of nature, to cross paths with other people, to listen to them and to take account of what was happening in the world from a close distance. To feel the wind, touch the earth, to be moved by what was taking place around me. So I did. Without too much planning but with a goal in mind, a gathering of nomads in the south of France, a project called The Nomadic Village where for two weeks artists from around the world would gather to form a temporary settlement and explore what it means to be a nomad these days. It was a long solo walk but I didn’t walk alone. I had asked through the social media if anybody wanted to adopt one of my walking days, walk with me in spirit, give me something to get me through the day. People responded from everywhere. I received encouraging words, poetry, addresses for shelter on the road, music to listen to, money as well, and often with a special request: to celebrate the birthday of a deceased parent, to look at a specific star constellation on that day, to think about a repressed nation, to look out for a particular bird, to take over a mother’s worries about her unborn child for twenty-four hours, to write haiku poetry.

Every day I started by embroidering the name of the person who was “walking” with me on the inside of my jacket. At the end of the day I wrote a story and dedicated it to him or her. Some days people actually joined me and walked with me in real but most days I was on my own or in the company of people I encountered on the road. Slow and only here and now but at the same time everywhere all the time: my mobile internet and my solar powered iPad made it possible to be in the online world as well and put my stories, which were just as much other peoples’ stories, out there. I had embroidered a QR code on my trousers and scanning it with a mobile device brought you to my blog.

names

forestbed

The suit is always my interface between the worlds I move through. Between the land I walk and the body I walk it with, the place people refer to as ‘the real world’, but which I consider to be just as real as the other world I move around in, the ephemeral world wide web. The stories I encounter, held in my hand, find a new home in the suit. From there they move into the other world.

The suit isn’t just practical. Apart from protecting me from wind, from sun and from insects, apart from being my canvas, it is a uniform as well, a costume. It opens up conversations, it makes people curious and I discovered that the suit allowed me to be anybody I wanted to be or more interesting: anybody people wanted me to be. I could roll up my trousers and my sleeves, unbutton my waistcoat and look like a tramp, I could button up my shirt and tuck it in neatly, look formal and enter a fancy place without any problem. I could look feminin or masculine, like a business woman or an artist. Walking though the fields or a city with everything I needed on my back it would trigger peoples’ curiosity and they would ask what I was doing. But often they wouldn’t look at me properly and have their opinion ready, based on what they thought they saw. In the breakfast room of a hostel, seated behind a table with my small iPad, books and electronic gear I was taken for a person on a business trip, even though my clothes were wrinkled and stained. In the restaurant where all the tables were set with heavy silverware and folded napkins and I couldn’t afford more than just a simple pasta dish, the waiter treated me with respect even though I had soil under my finger nails. The men in the cafe and carrier pigeon headquarters in a small village in Belgium laughed at me when I entered on a Sunday morning and asked, while drinking their beer and slapping each other on the back, “Where is your horse?”, but when I told them I was on foot and still had a long way to go they payed for my coffee and even gave me some money to keep me going.

I call my suit my soft armour. It keeps me safe and sound. It opens doors, it allows me to make connections. I can hide in it, be completely transparant in it, be nobody or anybody. I can be myself in it. In his book Walden, Henry David Thoreau wrote “I say, beware of all enterprises that require new clothes, and not rather a new wearer of clothes. If there is not a new man, how can the new clothes be made to fit? If you have any enterprise before you, try it in your old clothes. All men want, not something to do with, but something to do, or rather something to be. Perhaps we should never procure a new suit, however ragged or dirty the old, until we have so conducted, so enterprised or sailed in some way, that we feel like new men in the old, and that to retain it would be like keeping new wine in old bottles.” I do acquire a new suit for most walks but only after the old one has gone through a long wearing process and I feel ready for a new project. I once wore a suit for a full year. I once walked naked through the streets of a city after I had walked in the same suit for 108 days. Every day I embroidered a drawing on the inside and posted an image online of me in the suit in the place where I had moved through that day. When I felt it was time to take it off, I walked without it, in what is called a birthday suit. The skin you are born in.

Not long after, I had those words tattooed on my shoulder. A soft armour.

embroidery

tattoo

“Is there a specific meaning in walking as a woman in a male suit?” people sometimes ask. “Are you a lesbian?” has been one of the questions posed. “Isn’t it an anti-social act to retrieve from the normal world and leave everything behind?” a journalist wondered. “Is it appropriate to walk as an artistic act when there are so many refugees on the road who left their homes because they had no choice?” “Do you really think we should all return to live in a primitive way?”, often accompanied by a cynical smile, or “How do you survive, what do you eat on the road?”

I have answers to all of those questions and sometimes they change according to the person who is asking them. The question itself often gives me more information about the person who is inquiring than the answer is providing information about me. Maybe I am walking in order to raise questions. To have the opportunity to talk about slowness, about sustainability, about politics, about taking care, about being attentive, about the really brave people out there. About listening more and better. About showing that you can do anything you want to do. About putting your trust in the world.

Of all the questions that are being asked when I am walking, the one that is asked most frequently, almost daily, is: “aren’t you afraid?” It is the most interesting question of all. I never hesitate answering that one and my answer is always the same. No, I am not. We sometimes seem to live in a world of fear, but that doesn’t mean the world is a fearful place or that we should be afraid. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t put our trust in nature and people. I feel at home in the world, no real harm ever happened to me while I was walking. Amazing things happened. Sad and painful things as well but there is no reason to fear that either.

I call my walks art projects but it doesn’t matter what they are or why I am doing it. To be honest, I am still not exactly sure why I walk. But I guess I am walking to figure that out. The answer is in my steps.

corn & street

corn & suit

Monique Besten (with links to all my walks): http://www.moniquebesten.nl/

Walk from Barcelona to Paris, COP21: https://asoftarmour6.blogspot.com/

Walking with trees: https://wherewewandered.blogspot.com/

Walk from Amsterdam to Cuges les Pins (Nomadic Village): https://asoftarmour.blogspot.com/

Walk from Amsterdam to Vienna: https://asoftarmour5.blogspot.com/

108 days in a suit: https://moniqueinasuit.blogspot.com/

A Plastic Journey: https://vimeo.com/51107116

The Walking Library: https://walkinglibraryproject.wordpress.com/

The Nomadic Village: http://www.nomadic.cd

Monique Besten is a nomadic artist, moving around in Europe and mainly at home where her feet are. She is doing site-specific projects around the world, working in different media. Her current focus is on long-distance performative walking, collecting stories on the road in a three-piece business suit, writing daily online and embroidering the account of her walk on her suit.