The Walking Library is a library that carries books by foot. Inaugurated in 2012, it is an ongoing art project created by Dee Heddon and Misha Myers that aims to bring together people, walking, books, and reading. For each edition of The Walking Library a collection of books is gathered, taken on a walk and read with members of the public. While some have involved the creation of temporary collections, more permanent ones were curated for Sideways festival of peripatetic art, Belgium (2012), The Bothy Project (2014), Women Walking (2016) and most recently for Wild City | fiadh-bhaile (2018). [1] Each book included in these editions of the Walking Library was selected on the basis of a personal suggestion made by the publicin response to a variation of the question ‘what book would you take for a walk?’ The question was refined and customised each time we asked it, ensuring a particular point of focus for the walk and stimulating a specific interaction between the group of people, books, and environment walked with and in. On the walks, participants were invited to choose a book from the library that they wanted to carry and read from at specific locations, which they also selected along the route. For example, on a walk with Walking Library for Women Walking, while we strolled beside the river Thames, we read from Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. This in situ reading prompted in turn a discussion about where the sea started and ended and how far the sea was from where we stood.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for a Wild City, 2018, Performance. Photo Credit: © Mhairi Law.

The gifting of donations or suggestions for books, and their subsequent reading in site-responsive locations, gives shape to the walks that carry each collection and the performances that liberate words from their pages. The following overview of these collections considers how this personalisation and singularity of the gift is held within a larger relational formation of the collective response as a defining attribute of the compositional logic of The Walking Library. Each permanent Walking Library that we have curated has been donated by us, in turn, to the commissioning organisation or to an organisation likely to make good use of the library’s specific content, continuing its ongoing journeys and stories. [2]

The question that has prompted each Walking Library is the question we asked ourselves when we first encountered repeated references to books taken on walks, particularly from the late eighteenth to nineteenth centuries:

In 1792, Dorothy Wordsworth wrote in a letter to Jane Pollard: ‘I rise about six every morning, and, as I have no companion, walk with a book till half past eight, if the weather permits.’ [3]

We wondered what forms of companionship the book offers, how the book facilitates different interactions and relationships between walking, reading, people and places today, as a form of mobile and spatial media.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Sideways, 2012, Performance. Photo Credit: Authors.

For Sideways we asked ‘What book would you take on a walk across Belgium?

Sideways was an itinerant art festival that walked 334 km across Belgium, from August 17 to September 17 2012, using a network of underused, and in places disappeared footpaths, that offer alternatives to the country’s dense and expanding road networks. As Sideways aimed to connect ecology and culture, so too did the contents of our library, which included a selection of 90 books from the 200 suggestions received. While trying to classify this collection according to the Dewey Decimal system, a process undertaken for this library with the assistance of a professional librarian, we found the collection gathered revealed a different logic of its own:

i) walking as a genre of biographical literature and scholarly focus e.g. Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes by Robert Louis Stevenson, Wanderlust, A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit and The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald

ii) walking as a significant aspect within a fictional story e.g. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities

iii) the cultural context of this walk e.g. The Adventures of Tintin by Herge and Tom Butcher’s Blood River;

iv) writing that seemed to need or would benefit from being walked e.g. The Blue Hour by Carolyn Forché (“The long poem needs to be read when you're on the move, getting lots of fresh air - the words get into your bloodstream - they start to live there.”) and Emma Donoghue’s The Room (“It's such a horrible book to read and so claustrophobic you can't breathe. So probably the best place to read such a book is in the open air.”)

v) ‘practical’ books for our walk e.g. Identifying European Trees; and, finally,

vi) books that, like the festival itself, dwell onways that humans might dwell on earth better e.g. David Abram’s Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology.

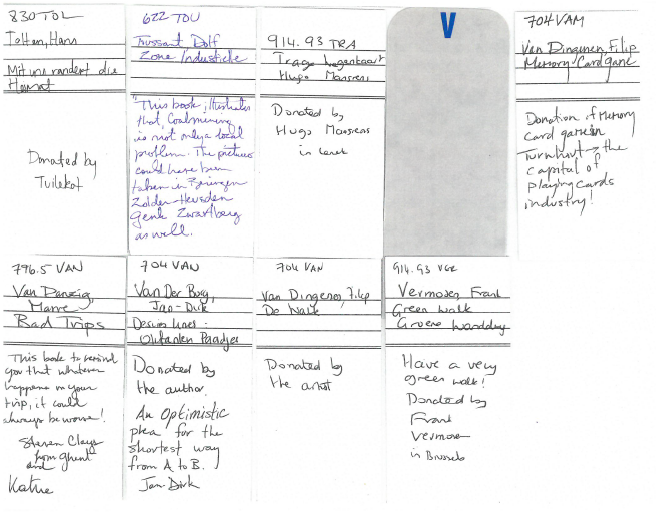

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Sideways, 2012, Catalogue. Photo Credit: Authors.

As evidenced in the two rationales included above, the reasons given for each suggestion offer insight into the personal thought behind each suggestion and how they contribute to the overall logic of the collection. These were inscribed on library cards and attached to the inside covers of books:

My book would have to be by Robert Louis Stevenson, because he is simply the best of companions for me, since childhood, and though I would like to take Kidnapped, or VriginibusPuerisque, or his extraordinary letters, the book would be Journeys with a Donkey in the Cevennes. It's probably a bit of a cheat (by him), like all he wrote it has an eye to the mainstream and the popular, & half of it may not be true at all, but it has soul (as he did), in a way that makes you journey with him, so let it be that amongst the many, many it could be.

Revealed often was the challenge of choice, of selecting the one book that would need to earn its place in being carried, and which would provide fitting companionship. Other considerations included the practicalities of walking with a book, demonstrated in these precise reasonsfor suggesting The Outing by Dylan Thomas:

Quite a few reasons why I like it, but for general circulation, it’s energetic, rhythmic and particularly absorbing when it’s wet! Mind you, as a hardback, it’s extremely small/light, so good in a rucksack!

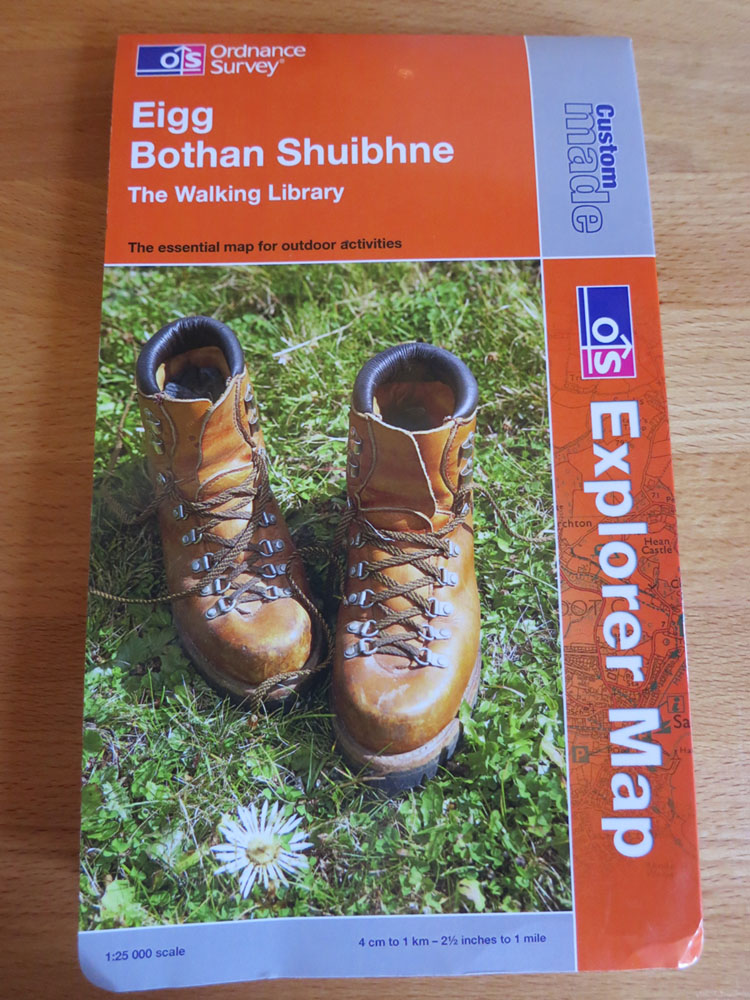

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Bothan Shibne, 2013, Walking Library Map. Photo Credit: Authors.

In 2013 we were commissioned by The Bothy Project to make The Walking Library for Bothan Shuibhne (14-15 June 2013), a library for Sweeney’s Bothy, an artist retreat on the Isle of Eigg.[4] Creating a walking library for this context prompted the following refinements of our initial question:

What book would you carry to Bothan Shuibhne – wherever you imagine it to be – for both the journey and your arrival? What book would provide you with shelter? Of solitude or companionship? To guide or get lost with? With spines upturned they too shelter worlds. Books as bricks, sometimes as heavy. Leaves that shade. Windows, hearths and thresholds to other times and places.

The first walk taken with the library for Bothan Shuibhne did not actually carry us to the bothy on Eigg, a community owned Hebridean island which has installed the world’s first completely wind, water and sun-powered electricity grid. Instead, we kept this destination in mind as we invited people to walk with us and donate a book to The Walking Library, which would, in turn, be installed in the bothy. This walk took place over two days (14-15 June 2013), starting at Carbeth Huts, a community company that fought and won a long battle to ensure the stewardship of an off-grid hutting environment, and ending at the Walled Garden, an artist-run venture transforming temporarily an abandoned industrial space on the outskirts of the city centre of Glasgow into a multi-purpose, outdoor performance space.

A collective constellation was made through the associative network of places and of readings; from the collection that came together through each of the walkers’ gifted books we held a vision of the bothy and the future artists that would retreat there. The following are some of the titles and the reasons given included in the small collection created for the modest refuge on Eigg. They reveal how Sweeney’s Bothy, and what might take shape there, was imagined through the offerings of the walkers:

Eigg Bothan Shuibhne OS Map – “A map to read at leisure, to wonder about who has wandered here over the centuries before”.

From Kyoto to Carbeth: poems and plants from the hills (Gerry Loose and Takaya Fujii): “For walking, for collaboration, for plants, for tasking, for huts, for starting points.”

The Path to the Sea (Thomas A Clark) – “I imagine this volume of Clarke’s poetry describes similar landscapes, vegetation, animal life, states of mind that a Sweeney-like wanderer might encounter on Eigg. He writes of islands, blue skies and shape shifting.”

Walking (Henry David Thoreau) – “because it’s a passionate treatise – manifesto – of walking and Thoreau is such a Romantic at heart”.

Journeys of Simplicity: Travelling Light (Philip Harden) – “There’s some lessons to be learnt from those who travelled light. What do we need when we travel? What can/should/will we leave behind?”

You Are Not a Stranger Here (Adam Haslett) – “This collection of short stories is haunting. A fantastic way to end a walk – stories that will carry you in quiet solitude when you begin to walk once again”.

Courts of Air and Earth (Trevor Joyce) – “For its relation to the Sweeney myth. Joyce is one of the key translators of Sweeney. These translations are included here.”

Ecology of Wisdom (Arne Naess) – “chosen for its insights on ‘deep ecology’ and the ethics of wildness. Relates to Sweeney’s Bothy”.

The Poetics of Space (Gaston Bachelard) – “Because it talks of the ‘hut dream’”; “Classic writing on space and memory”.

The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories (Brunzo Schultz) – “This is a book of wonder and strangeness. Very human, often funny and miraculously brought to the stage by Theatre de Complicite in their adaptation. A glorious and moving experience and so good for a wet and cold evening in the bothy.”

Nineteen Eighty Four (George Orwell) – “George Orwell wrote 1984 in a very remote house called Barnhill which is on the north east tip of the isle of Jura. It’s interesting to know the context of how this book came to be as this copy might next get read in a far off place, or a wee bothy. In going away to escape the rushes of the city Orwell was able to write from a different view.”

The collection assembled for Bothan Shuibhne reveals the form of a companionship designed to

-

find inspiration and company in the solitude of fellow artists;

-

offer ways to attend to other forms of life and dwelling in wild places;

-

inform how to make do and get making with little distraction or comfort.

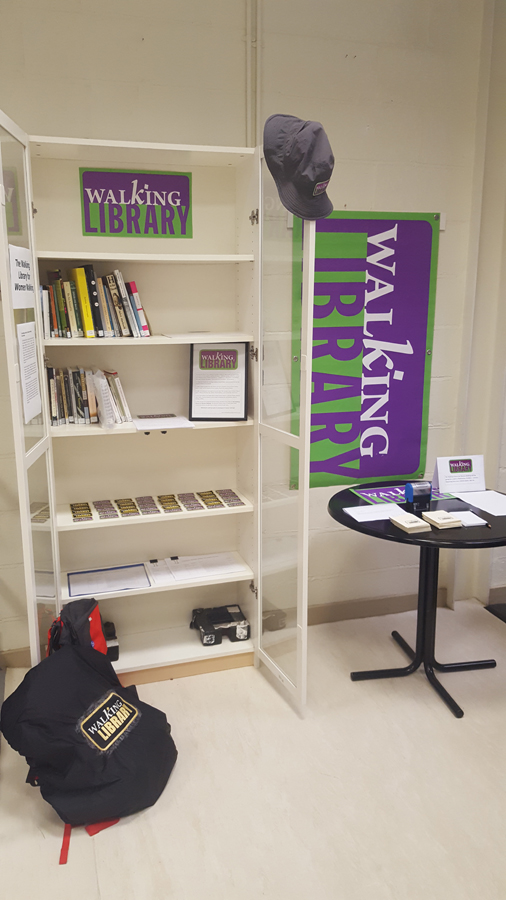

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Walking Women, 2016, Installation. Photo Credit: Authors.

In 2016, The Walking Library for Women Walking (WLfWW) was created as part of Walking Women, a UK national event curated by artists Clare Qualmann and Amy Sharrocks. This library received 119 donated books.

Three walks were taken with the library as part of the Walking Women events, two in London and one in Edinburgh. It was also walked in Bristol, Glasgow and Newcastle, was installed in the exhibition, The House that Heals the Soul (Centre for Contemporary Art, Glasgow) from 22 July - 3 September 2017 and a temporary WLfWW library was created for ‘Moving Out of Door’, an event held in Geelong, Australia, in November 2017.

Each of the WLfWW walks retraced suffragette marches and actions and expressed, as the suffragettes did before us, women’s right to take up and create public space through their collective power and physical presence. To create the collection taken on these walks we asked:

What book would you recommend to a woman going for a walk; a book that might provide excellent company, inspiration, solace, advice, humour, information…?

These walks garneredthat collective power, also expressed throughthe collection’s specific taxonomy that followed from the combined responses to this question. As we have noted in a forthcoming essay about this Walking Library, the collection includes:

i) artists’ books, most often donated by the artist, most often a woman

ii) factual and scholarly books about walking, many by women

iii) environmental writing, most of it written by women

iv) published letters and journals of significant women who have some connection with walking or journeying

v) memoirs of women deemed inspirational, many of them related to walking

vi) novels by women which feature walking

vii) books by women which have autobiographical significance for the donator

viii) and books which seem to need to be walked to come fully into their own. [5]

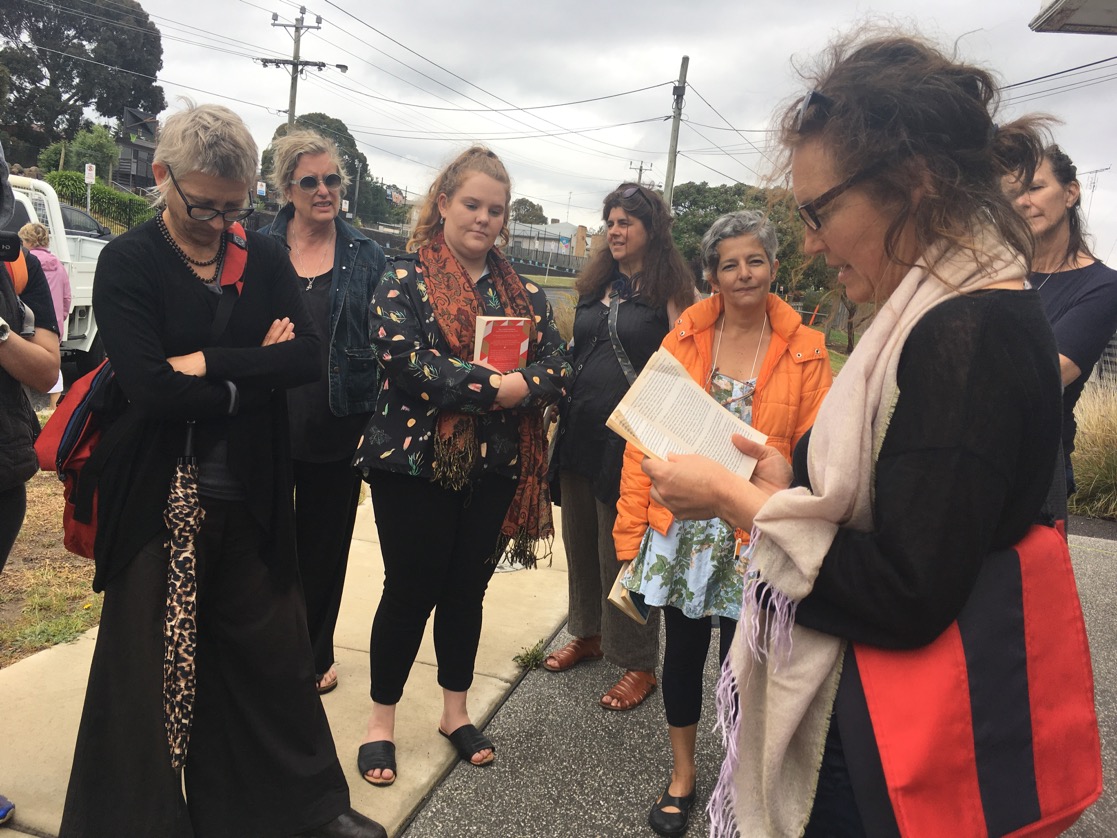

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Walking Women, Geelong, 2018, Performance. Photo credit: Authors.

Donations ranged from early writings by women, such as The Pillow Book of SeiShonagon (“Partly because it's in small chunks that you can absorb along with a biscuit as you rest from your walk and also because it's the Thoughts And Opinions of an actual woman from more than a thousand years ago.” to first feminist book written (Simone de Beauvoir’s Blood of Others) to play texts (Caryl Churchill’s play Blue Heart because “I wanted to find a non-naturalistic performance text, something that needed to be discovered and understood through rhythm. I think [this] needs the SPACE to work through the text in both head and body. So, a combination of reading and walking seemed right.”) What The Walking Library for Women Walking drives home is that there is no single answer to the prompting question; we are endlessly surprised by the diversity of our collection and our taxonomies are only partly successful in creating seeming order and coherency. Browsing our shelves in search of a book to carry offers a surprising journey in itself.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for a Wild City, 2018, Installation. Photo Credit: © Mhairi Law.

The most recent Walking Library is for a Wild City | fiadh-bhaile (2018) a collaboration between The Walking Library and artist Alec Finlay, and conceived for Festival 2018, the cultural and arts programme running as part of the Glasgow 2018 European Championships. This project aims to explore the nature of an urban setting, to reflect on what wild means in a city context, to discover what a wild city is and imagine what it might become. For this library we asked for suggestions in response to the following questions:

What book reveals wildness in the city?

What book would you rewild by walking?

The books that people have suggested for this library for both adults and children range wildly too, from those which help us see what is sometimes overlooked or under-acknowledged- e.g. the variety of wild things growing in vacant lots or the secret lives of pigeons - to dystopian apocalyptic fictionwhere cities are destroyed but nature survives and helpful pocketguides to urban foraging.

As we walk and read and look and sense together we hope to re-map this “dear green city” of Glasgow – the green howe -- and rediscover the significance of old names – Sauchiehall Street, willowhaugh; the Kelvin, the reedy river – as a prompt to the invention of new ones.

At the time of writing, we have only just begun the walking research of this latest library edition, with the first of these walks taking place on the 13th and 26thMay, meandering through the Barras to Arcadia Street in the East of the city and from Festival Park to Plantation Park in the South. We have witnessed ‘urban jungles’ growing behind the facades of empty buildings, buddleia persisting in the most seemingly inhospitable cracks, mussel shells on the pavements (perhaps cast-offs from drunken human revelers after a wild night on the town rather than those of joyfully feasting urban seagulls). As we walk these familiar streets with a newly sharpened (insect) antennae, we reclaim and rewild them: ‘Dandelion Daunder’ and ‘Piss-the-Bed Verge’, ‘Windowed Wilding Garden’ and ‘Copper Beech Row’, ‘Kite Green’ and ‘Buddleia Bog’. Alec draws maps of the walks tracing these imagined names (indicated with single quotes), books read, things spotted (marked with boxes around the text), and views of things off the edges of the map (designated by arrows). These drawings will continue to multiply, aswill our imaginings, readings and sightings as we walk throughout the rest of Wild City; they will come together into a book that will be the final addition to the collection, but one that makes these routes available as a legacy for others to follow.

Each Walking Library edition responds to the contexts of its walking and of its walkers. We have come to understand it as a momentary, site-responsive manifestation which depends upon and promotes the library’s social capacities -- gifting, lending and borrowing – to design and manifest the assemblage and circulation of its collections of books. Our library activates the sociable, mobile and spatial endowments of the book that make it such a pliable media for the possibility of journeys and stories and places to converge. Perhaps these capacities are what makes the book such an enduring convivial companion so readily shared. Each iteration of the starting question, refined to suit the context of each Walking Library journey and to curate its one-of-a-kind assemblage of books, endeavors to reiterate that conviviality, a gifting impulse that sets in motion unexpected interconnections between multiple lines of thought, text, steps and locations. As these permanent collections follow the course of that impulse and their unique taxonomic logic, we wonder what further journeys, stories and places will be walked, read and imagined into existence through their companionship.

Misha Myers is Course Leader of Creative Arts at Deakin University in Melbourne. Her practice-based research is generally collaborative in process, drawing in culturally diverse participants to work together to facilitate social change through located and cross platform arts-based enquiry often enabled by digital technologies and walking. She is the author of many articles, chapters and essays on walking aesthetics, locative media and digital performance.

Deirdre Heddon holds the James Arnott Chair in Drama at the University of Glasgow. She is the author of many monographs, articles and essays, including Autobiography and Performance (2008), and has co-edited a number of collections including, most recently, It's All Allowed: The Performances of Adrian Howells (2016). She is currently working on Performing Forests, a monograph for Performing Landscapes, a new series for which she is co-editor with Sally Mackey.

Endnotes

[1] More detailed consideration is given to the historical contexts of libraries and reading and the interaction between reading in situ and walking in Deirdre Heddon and Misha Myers (2017), The walking library: mobilising books, places, readers and reading. Performance Research, 22(1), pp. 32-48. A full account of the Walking Library for Sideways is available in Deirdre Heddon and Misha Myers (2014), Stories from the walking library. Cultural Geographies, 21(4), pp. 639-655.

[2] The Walking Library for Sideways was commissioned by and donated to Sideways Festival; The Walking Library for Sweeney’s Bothy was commissioned by and donated to the Bothy Project; The Walking Library for Women Walking was created for Women Walking and donated to Glasgow Women’s Library. The final book added to each library is one made by us which documents its multiple stories and pathways.

[3] Cited in Morris Marples (1959), Shanks’s Pony: A Study of Walking, London: Dent, p.88.

[4] The eponymous Sweeney was an Ulster King and central figure of the Irish saga, thought to have been written in the fourteenth century, called Buile Suibhne (translated variously as Sweeney Astray, and Sweeney, Peregrine), which tells of how Sweeney’s offense of a Christian priest led to a curse put upon him to live only in the wild places of Ireland and western Scotland, shunning human company and seeking out remoteness wherever it could be found.

[5] Deirdre Heddon and Misha Myers (forthcoming).The Walking Library for Women Walking. In Walking, Landscape and Environment, eds. David Borthwick, Pippa Marland and Anna Stenning, London: Routledge.

List of Images

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for a Wild City, 2018, Performance. Photo Credit: © Mhairi Law.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Sideways, 2012, Performance. Photo Credit: Authors.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Sideways, 2012, Catalogue. Photo Credit: Authors.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Bothan Shibne, 2013, Walking Library Map.Photo Credit: Authors.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Walking Women, 2016, Installation.Photo Credit: Authors.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for Walking Women, Geelong, 2018, Performance.Photo credit: Authors.

Dee Heddon & Misha Myers, Walking Library for a Wild City, 2018, Installation. Photo Credit: © Mhairi Law.

Alec Finlay, Walking Library for a Wild City, 2018, Drawing. Image Credit: © Alec Finlay.