Tracing the line of the aqueduct. Photo: Matteo Guidi

Late in the autumn of 2012, a group of six researchers and artists set out on foot across the West Bank, starting near al-Arroub, a Palestinian refugee camp in the southern lobe of the West Bank. There lies a magnificent stone pool carved into the ground in the era of the Roman Empire. From al-Arroub the group started walking towards Solomon’s Pools, another three massive stone reservoirs just south of Bethlehem, attempting to follow the scuttling cord of a Roman aqueduct connecting the two locations. I joined them on their second day.[1]

The valleys between al-Arroub and Jerusalem hold several Palestinian towns and villages. Bethlehem, a city of 220,000 residents south of Jerusalem, is the largest urban center along the route. A number of scattered but networked Israeli colonies jut across the hilltops.

Our hike fell around the olive harvest season in late autumn; aged tree trunks thickened our view of the agricultural lands we passed. For the most part we kept to rocky and barren routes between patches of yellow thistle or followed any roadways heading in our direction.

Charting our way across the hilly terrain in search of the elusive remains, we looked for clues — the flow of the topography, rocks hand-hewn for ancient piping. Excavating a forgotten path, we reconstructed the aqueduct in our imaginations. But we also reconstructed the continuity of a rolling Palestinian landscape interrupted by the spatial legacy of Israeli rule.

Participants trek across the ridge of a quarry. Quarrying is one of the most lucrative industries in the West Bank. Photo: Matteo Guidi

The most visible aspect of this legacy is what is called the separation or annexation Wall in progress since 2002, which strays far from the 1967 ceasefire line (the “Green Line”), carving out 10% of the West Bank through de facto annexation into Israel proper. Other and less visible boundaries crisscross the landscape, inscribing Israel’s claim to the terrain. The language of the Israeli occupation designates certain lands as off-limits to Palestinian residents with terms such as “military zones”, “seam zones” or “firing zones”, and follows an alphabetical terminology of Areas A, B and C to describe degrees of military administration and rule.

The hike dealt with none of these lines directly, but offered a subversive challenge by stepping into a time before the current apartheid-reality existed: before the Wall, before the colonial parceling of Palestine, before the displacement of 800,000 Palestinians in the Nakba (catastrophe) of 1947-1949. In particular, it explored the im/possibility of spatial continuity in Palestine.

Undergirding the trek was the act of stitching together a fractured social geography. The (mostly) invisible political lines dropped across the hills by empires, states and international law writhed underfoot constantly compelling one to reflect on who is within and who is the “outsider”.

The dating of the Arrub Aqueduct is not certain, but it is a good candidate for the aqueduct mentioned by Josephus for which Pontius Pilate appropriated Temple funds, thereby sparking riots in Jerusalem (Antiquities 18). It seemingly was re-built in the Mamluk period and finally went out of service in Ottoman times. (Its great length made it especially susceptible to damage or clogging, unauthorized tapping of the water, and the pilfering of cap-stones.)[2]

CONNECTING THE CAMPS

The path of the aqueduct snaked across the hillsides and so did we. In all, we could follow exposed piping for only thirty minutes of the two-day trek. Photo: Matteo Guidi

The hiking project, entitled “In Between Camps”, emerged from Bethlehem-based Campus in Camps, a program developed by Al-Quds University, an experimental educational program in the refugee camp of al-Dheisheh.[3] Its foundational philosophy is to foster new forms of self-representation amongst Palestinian refugees. As one of the participants of the “university in exile’s” curriculum, Saleh Khannah initiated the hiking project, primarily in order to ‘reactivate’ the site of the Roman pool near his home of al-Arroub refugee camp.

Al-Arroub is today home to 8,000 people from 33 Palestinian villages depopulated in the 1948 War. Most residents come from Iraq Al-Manshiyya, Zakariyya, Aggour and Qustantinya villages. The name al-Arroub means “fresh water” referring to the plentiful springs of the area where the camp was initially set up to temporarily shelter the refugees fleeing the war. The original refugees and their descendants have sought their right to return and repatriation since those days. The right of return is a core international legal right of forcibly displaced people (66% of the global Palestinian population falls into this category), although without enforcement mechanisms or political will that right is denied to Palestinians by Israel with international complicity.

Saleh was born and raised in al-Arroub, though his family was forcibly displaced from Zakariyya in 1948. He is one of 4.8 million Palestinian refugees registered by the United Nations Relief Works Agency’s (UNRWA); another estimated 2.6 million Palestinian refugees are not counted by UNRWA.[4]

For Saleh and the project’s other visionaries, the hike intended to explore the concept of relation. In a booklet compiled by participants, Giuliana Racco writes: “The ancient structure (now for the most part destroyed) places two contemporary camps, Arroub (near Hebron) and Dheisheh (near Bethlehem), in relation to one another, and these camps are likewise both related to Jerusalem via this conduit constructed by the Romans — ancient colonizers of the area — crossing territories which are at times prohibited to the locals — Palestinians, due to the current situation of rule.” Physically tracing one of the arteries of a once vast water system covering the territory of what is now Palestine/Israel was also an exploration into the al-Arroub pool.

The al-Arroub pool. Photo: Matteo Guidi

A “CAREFUL” ENCOUNTER

Due to severe segregation, the reality for Palestinians in the West Bank is one of extremely limited contact with Israelis composed either by looking from afar at colonizers on the hilltops or exchanges with soldiers enforcing the occupation. Those West Bank Palestinians with the most intimate experience with Israelis have spent time in prison. The proximity to and relations with Israelis vary in other sub-territories of Palestine.

At the end of the first day of the hike, two Israeli military jeeps suddenly appeared from the roadside. Four soldiers emerged and approached the group asking what the seemingly out-of-place hikers were doing and where they were from.

One of the internationals amongst the hikers responded to the soldiers’ enquiries: “We are from Italy”, said Diego. The soldiers were noticeably suspicious, particularly apparent when they stared at the Palestinians, profiling them by their skin tone and dress. The group applied a tactic of information overload: we are hiking … in search of an ancient Roman aqueduct … look, here is a map …

Techniques of Distraction. Photo: Ismail Albis

The soldiers did not request anyone’s identification cards nor did they offer any useful suggestions for the hikers’ search. The outcome of the interaction was to continue unhindered. “They gave us one piece of advice,” said Saleh: “They told us to be careful. I understood it as, ‘be careful of Palestinians.'”

An Italian and a Palestinian hiker regard an escarpment. Photo: Matteo Guidi

LINES OF FLIGHT, LINES OF SEPARATION

In the 1977 Dialogues, French philosopher Gilles Deleuze wrote: “in a certain sense … what is primary in a society are the lines, the movements of flight … in a society, everything flees … a society is defined by its lines of flight.” As a whole but to varying degrees, Palestinians are pressured to flee while Jewish Israelis are encouraged to replace them.

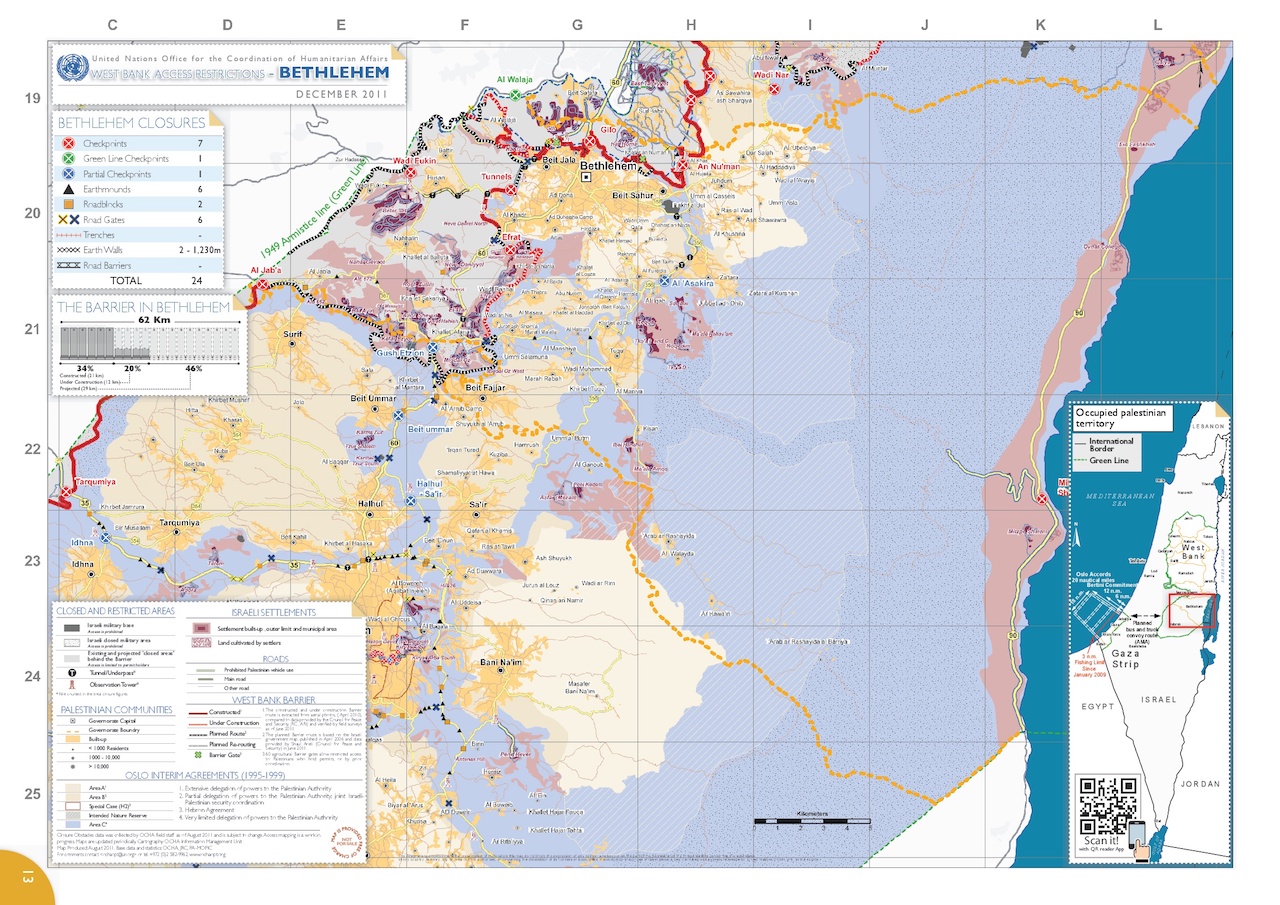

At a public lecture in 2012 in Beit Sahour, Palestine, Nurit Peled-Elhanan, an Israeli academic who has written on the presentation of Palestinians in Israeli schoolbooks, stated that maps — representations of these lines of flight — “are political tools that transmit the messages they intend to transmit.” The tangled borders Israel dictates are primarily purposed with reinforcing the separation of types according to a gradient of rights.

Zooming in on Jerusalem shows the limited mandate of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) ending at the increasingly irrelevant 1967 Green Line. UN maps are regularly updated in response to Israel’s expanding settlement projects; this map was produced in December 2011.

Despite the seeming solidity of the lines as they appear on maps, Israel has never declared its borders, enabling it to continue territorial expansion without revising political positions. Vague official borders are paired with an elaborate system of displacement and separation practices. In the West Bank, a regime of checkpoints and permits is designed to bar Palestinians from the territory Israel currently colonizes and restrict Palestinian use of the territory it intends to colonize in the future. The regime often manufactures mixed messages like the “security fence.” In practice, the Annexation Wall embodies imprisonment and land confiscation at the cost of human security while delineating an ‘us’ from a ‘them.’ Enforced human classification, obvious to the disenfranchised, betrays the public persona of the state.

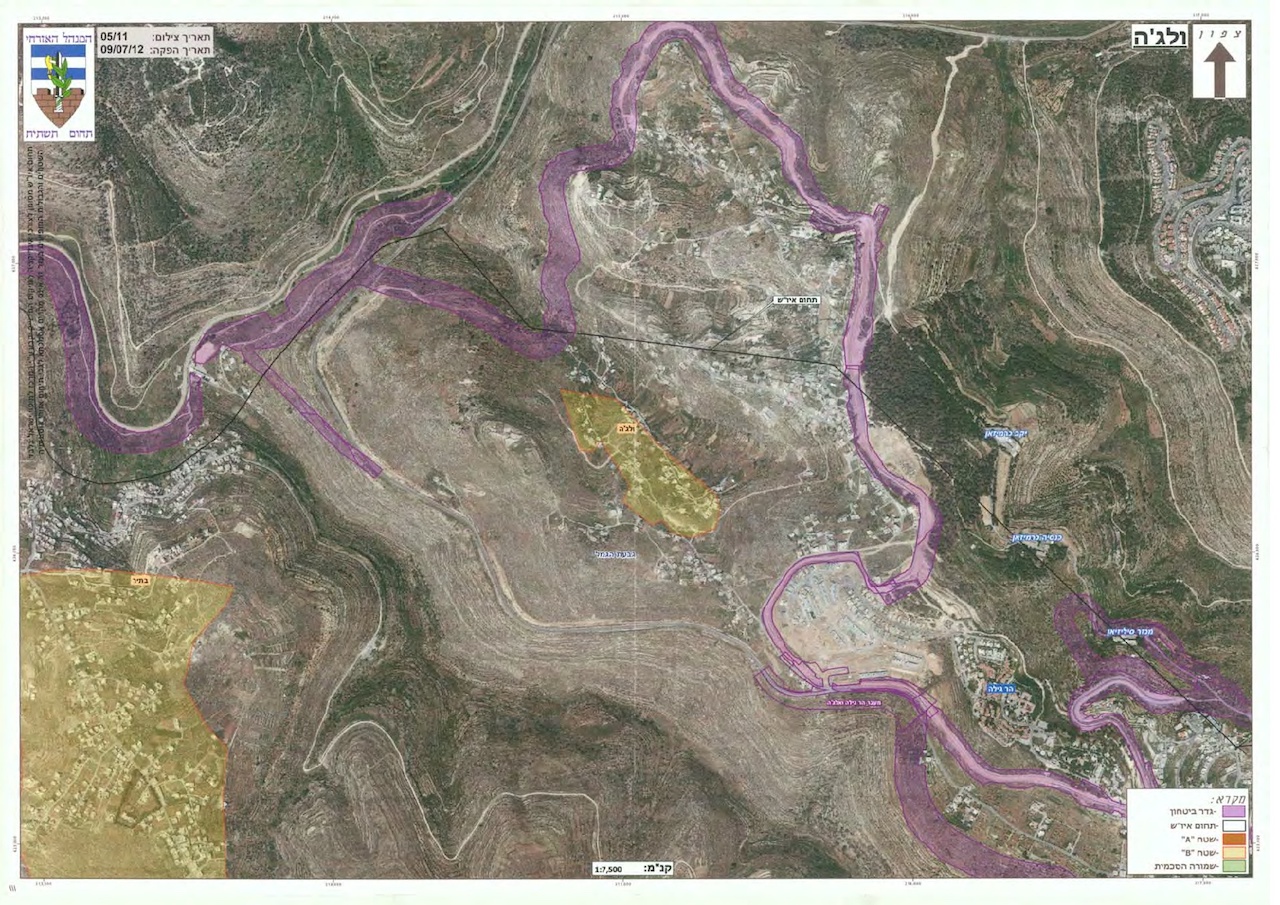

A map of the West Bank village of al-Walaja released by Israel in July 2012 shows the intended and in-progress plan for the Wall that will encircle the residents, isolating one home in an individual prison accessible by tunnel and place two homes within a concrete corridor. The purple areas represent the wall of annexation.

The Oslo negotiations between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization during the 1990s shaded the map of the West Bank into Areas A, B and C where the newly created Palestinian Authority and Israel have since collaborated on administrative and military control of the territory. The cartographic partitions are embedded with legal triggers such as the prohibition of Israeli citizens from Area A of the West Bank (18% of the territory, where most West Bank Palestinians live and which is under the administration of the Palestinian Authority). While in practice Israel rarely enforces this restriction for Palestinian citizens of Israel, mixed-demographic Palestinians are officially prohibited from group hikes across this network of geographic separation.

An extract of the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement map from the 1995 Oslo Agreement, depicting Areas A and B of the West Bank. Jerusalem is in the center, Hebron to the southwest, Ramallah to the north and Jericho to the northeast.

Saleh’s band of hikers was composed of foreign passport holders, West Bank Palestinian residency card holders and myself, a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship. The hikers were united by a shared experience, but technically each individual faced specific restrictions based on the lines of the contemporary political map that they crossed. Palestinian citizens of Israel are prohibited from entering Area A, which is “dangerous” according to the Israeli signs positioned as helpful reminders. West Bank Palestinians are forbidden from entering Israel proper which, unlike the restriction on citizens in Area A, is enforced with rigidity. Foreigners are permitted everywhere in Palestine/Israel except the Gaza Strip, but are advised to avoid mention of travel to the West Bank when passing through the Tel Aviv airport.

Israel categorizes Palestinians under its control into four groups on a spectrum of relatively more rights to none: citizens of Israel, Jerusalem residents, West Bank residents, Gaza Strip residents and the fifth non-category of exiled refugees, dispossessed of any rights to their homeland. This contrasts with the status of Jewish people in Israel who hold citizenship and nationality. While these are often synonymous terms in other countries, full national rights are categorically unattainable for Palestinians and constitute the linchpin of the system of race-based rule.[5]

With adjustment, the Israeli demarcation sign reads: “This road leads to [the] Palestinian village [of Tuqu’.] The entrance for Israeli citizens is dangerous [undermines our policy of segregation].” Photo: Thayer Hastings

The problematic position of Palestinian citizens of Israel evokes one of the most convoluted messages of the Israeli regime. 1.7 million Palestinian citizens are legally and socially unequal to Jewish Israelis despite their citizenship. More than 60 Israeli laws discriminate against them in all areas of life.[6] For example, the Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law specifically targets Palestinians by refusing them the right to family unification.[7] Palestinian spouses from the West Bank or the Gaza Strip are prohibited citizenship, residency or permits required for crossing the Green Line into Israel. Paired with the prohibition of Palestinian citizens from Area A of the West Bank and the absolute disconnect from Gaza by the military siege, the Israeli legal system effectively forbids coupling across the three political territories within the homeland.

An Israeli signpost on the border of Firing Zone 918 in the hills South of Hebron. Photo: Thayer Hastings

Israeli legal code and spatial boundaries are parallel institutions of exclusion targeting Palestinians across political environs. Even in so-called ‘mixed’ cities like Haifa, Palestinians and Israelis live largely separate lives. Israel’s mixed spaces are rooted in the settlement-on-the-hill mentality imbedding separation in a way fundamentally analogous to the segregated planning of West Bank communities.

Unlike Palestinians, Jewish-Israelis are encouraged to live a seamless existence within a contiguous “Greater Israel” complete with highway infrastructure linking West Bank settler colonies to Israel proper without exposure to Palestinian urbanity. The arrangement results in a semblance of contiguity for Jewish-Israeli citizens. For Palestinians, however, the Green Line is solid. While thousands of Palestinian families defy the separation principle embedded in the Citizenship Law, many others are effectively expelled from the country due to a combination of factors that make life unbearable.

The state justifies physical and legal separation with arguments about “security”, but unravelling the rhetoric reveals mechanisms coordinated to secure specific demographic outcomes. In total, the Israeli ethnocratic system, the Wall and other barriers fracture the seven million Palestinians currently within Palestine/Israel into more manageable political and economic entities while encouraging their emigration from “Greater Israel”. Most of the boundaries depicted on contemporary maps are spaces of encroaching colonization and, on the other hand, forced expulsion. Since 1947, waves of displacement have torn through Palestinian society, and as a result, six million Palestinians reside in the Shatat, in exile, outside of Palestine/Israel.

UNDER ABNORMAL URBANISM, A FRACTURED RETURN

On the second day I joined the hikers in Tuqu’ village south of Bethlehem. Stumbling gradually into wakefulness in the early morning sunlight, we spread into the hills searching anew for signs of the aqueduct. After a few false starts we decided to head in the general direction we believed the water system to be, inevitably encountering the area’s residents. Saleh tasked himself with determining the most knowledgeable-looking individuals to ask for directions. They were almost always elderly male farmers. We met an aged man with missing teeth accompanied by his son of around 40 years. They were proudly familiar with the aqueduct and described a detailed walking route to a point where we would re-emerge in its tracks. They were right.

Saleh consults an elder for directions. Photo: Matteo Guidi.

At last, we reached Solomon’s Pools, a park area shaded by sturdy trees featuring three huge stone basins in a row that had once functioned as the main water vestibules for first century Bethlehem and, slightly further north, Jerusalem. The Palestinians of Irtas (the town where the pools are located) and Dheisheh (a nearby refugee camp), and picnicking visitors use the site as a public space, the lack of which is a defining feature of many densely populated and spatially restricted refugee camps. Solomon’s Pools Resort and Convention Center recently won a bid to develop a private park at the site, fundamentally altering the way the space will be used and, most importantly, who can use it.

Having hiked more than 40 kilometers over two days, on a third outing we made a return to al-Arroub’s Roman pool, the original site of the trek and Saleh’s home. There, we spent an afternoon cleaning the ancient pool. As Saleh put it, the pool is an underutilized venue. He envisioned transforming its current appearance as a crater in the landscape into a public space available for leisure, concerts and educational activities for the al-Arroub community inside the pool area, and surpassing the vision for the use of Solomon’s pools at the other end of the aqueduct. Although unattended and antiquated, the pool serves as a connection to a Palestine that precedes the current regime of rule and emphasizes a symbiotic relationship with what is a largely off limits Jerusalem.

A review of Arabic historical records revealed that the Al-Arrub aqueduct has been restored many times and the most important one was done by Qansawa Al Yahyawi in the year 1483 A.D.[8]

CONFRONTING AN ABNORMAL URBANISM

Intending to visit al-Arroub several weeks later, I was advised by Saleh not to come as Israeli soldiers were invading the camp on a daily basis, and that particular Sunday was exceptionally harsh with many cans of tear gas, sound bombs and rubber-coated bullets fired. Not long before, a 21-year-old woman, Lubna Munir al-Hanash, from the camp was killed by a live bullet to the head on January 23rd, 2013 when Israeli soldiers fired on her and her friend while they walked to their college campus.[9] I heeded Saleh’s advice and waited for the following week.

That following week, entering the camp from the main road, I passed two haughty Israeli soldiers who had paused to reload their guns with tear gas canisters. Probably because I looked like an outsider, they held off from firing until I had walked around the bend in the road and out of sight behind the houses. Around the curve were a dozen charged youth — mostly children — some of whom held rocks to ward off the soldiers.[10] The noxious gas was enough encouragement to hurry along without the concerned warnings from residents on the street. Once inside the office with Saleh and two other participants of the hike, we tightly shut the doors and windows against the stinging tear gas that had infested all corners of the camp.

In order to offer direction, the map we used for the hike long predated the political reality that exists today. Outdated enough to recognize the aqueduct’s path as a significant marker, the map also provided relief from the web of political lines that bind Palestinian space. The purpose of the project — to reactivate the water system’s source — was a modest objective with profound implications. Tracing geographic contiguity across the Palestinian hills reasserted a sense of belonging and confronted the ideology of dispossession built into the fracturing regulations imposed by Israel. By linking abnormal political spaces and challenging those boundaries, the process of hiking excavated layers of exclusion.

* Thayer Hastings is a writer and currently a PhD student of anthropology at The Graduate Center, CUNY in New York City. Follow him on Twitter @ThayerHastings.

**A version of this article was published by The Global Urbanist on 13 August 2013: http://globalurbanist.com/2013/08/13/tracing-a-line-palestine.

[1] The art project, In Between Camps, began with the extension of the simple action of walking. Over the course of two-days, participants in the walk searched for the traces of an ancient Roman waterway that once linked the springs of al-Arroub to Solomon’s Pools south of Bethlehem, finally bringing water to Jerusalem. Built by ancient colonizers, in a twist of fate, the aqueduct connects two contemporary refugee camps, winding its way through territories that are often restricted to those who inhabit the land. Walk participants included Ismael Al-bis, Fabio Franz, Matteo Guidi, Thayer Hastings, Ibrahim Jawabreh, Saleh Khannah, Sara Pelligrini, Giuliana Racco and Diego Segatto.

[2] Ya’akov Billig, “The Low-Level Aqueduct to Jerusalem: Recent Discoveries,” Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, 46 (2002).

[3] See Campus in Camps at http://www.campusincamps.ps/about/ and visit the project page of The Pool at http://www.campusincamps.ps/projects/04-the-pool/.

[4] BADIL Resource Center biennial Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons, 2010-2012: http://www.badil.org/en/press-releases/142-2012/3638-press-eng-53.

[5] For more see the reporting of Jonathan Cook, especially: “Why there are no ‘Israelis’ in the Jewish State,” https://www.jonathan-cook.net/2010-04-06/why-there-are-no-israelis-in-the-jewish-state/.

[6] See Adalah’s Discriminatory Laws Database: https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/7771.

[7] For more on this law, see: https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/511.

[8] Jamal M. Barghouth and Al-Sa’ed, Rashed M.Y., “Sustainability of Ancient Water Supply Facilities in Jerusalem,” Sustainability (2009) p. 1112.

[9] Al-Haq, “Six Palestinians Killed by Israeli Military in January,” 31 January 2013: http://www.alhaq.org/documentation/weekly-focuses/669-six-palestinians-killed-by-israeli-military-in-january.

[10] Read Amira Hass, “The Inner Syntax of Palestinian Stone-throwing,” in Ha’aretz on 3 April 2013: https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-amira-hass-the-inner-syntax-of-resistance-1.5236559.