Abstract:

In this essay, I will look at elements of my practice as both an artist and curator[1] that might be described as pilgrimages, explored through my role as Principle Investigator of WALK. My work draws on a ‘practice’ of walking, or more properly, meandering; meanders that seek to redress the bifurcation of culture and nature. Nature, in this inclusive sense, is inherently creative and fluid. These meanders take a human and embodied approach to being in the landscape - what Robert McFarlane calls “landscape and the human heart” (Macfarlane, 2012) [2] and are shared with others. My approach is phenomenological and much influenced by the work of Wylie (2007)[3] and Ingold (2010)[4]. The former stresses that “direct, bodily contact with, and experience of, landscape’ reveals ‘how senses of self and landscape are together made and communicated, in and through lived experience (Wylie, 2007).[5]

I will discuss an artistic intervention that develops and uses the notion of what I call conversive pilgrimage, focusing particularly on the natural history of a place because they often have fascinating and complex stories to tell that signpost and/or transcend social and political histories. I will argue that pilgrimages can help to bring us closer to the experience of what it is to be a part of a more-than-human world, undermining the deterritorialization of culture (Parkins and Craig, 2006)[6]. Following a short introduction about the idea and experience of pilgrimage the next part of my essay adopts a bricolage methodology – a series of linked, (one might say rhizomatic) notes and recollections of a number of exhibitions and pilgrimage walks curated and undertaken over the last twenty years, presented in a non-linear format; memories that collapse traditional ideas and experiences of time.

In Walking (1851)[7], Thoreau defines "the art of Walking" as "a genius … for sauntering," describing the etymology of saunter as derived from "a la Sainte Terre," that is ‘going to the Holy Land’. The walk, then, becomes a sort of pilgrimage, a kind of religious or quasi-religious ritual. Although not religious myself, I respect, and am interested in non-institutional religious thought and philosophy. I also share a view with many artists and writers/poets that our creative life is a journey of exploration and discovery - a pilgrimage of embodied, physical and creative reflection underlining that we are part of a more-than-human, creative world

---------------------------

Over recent years I have been involved in a number of exhibitions about art and walking that have included work that might loosely be said to be about pilgrimage of one form or another. For example, in Wordsworth and Basho: Walking Poets, I made a new piece based around a response to Dorothy Wordsworth’s ascent of Helvellyn in 1801. Dorothy walked incessantly (Collier 2014)[8] and I have followed many of the Lake District routes described in her journals. The Lake District is a cultural, rather than natural, landscape; its fell sides the result of forest clearances and sheep farming - a landscape sometimes described as Wordsworthshire’[9]. In my creative reworkings for the show, I selected journal entries that describe favourite routes Dorothy followed—including a walk ‘upon Helvellyn, glorious, glorious sights’.

Sunday 25th (October 1801)

…went upon Helvellyn, glorious

glorious sights – the sea at

Cartmel – The Scotch mountains

beyond the sea to the right –

Whiteside large & round & very

Soft & green behind us. Mists

Above & below & close to us,

With the Sun amongst them –

They shot down to the coves … [10]

I wanted my interventions to draw attention to her characteristically fresh powers of natural description.

In fact, Helvellyn has become a place of pilgrimage for me over many years, having climbed it countless times, often making two or three visits a year to its lofty summit via Striding Edge and returning along Swirral Edge (described by Wordsworth as its ‘blue Ether’s arms’); up the Pony Track from the Youth Hostel at Glenridding; from Patterdale, via Grizedale Tarn and over Dollywagon Pike or (the most direct route) from Thirlmere.

I have vivid memories of each of these journeys; of cloud inversions seen at the summit as the ridges of Lakeland mountains appear to ‘breach’ through the early morning mists (‘a thousand ridges … gleaming like a silver shield!’)[11]; of seeing Wheatear in the early spring, newly arrived from North Africa; a handsome bird (a favourite of mine), in flight it shows a white rump, hence one of its colloquial names – wittol, or white arse; the elusive white-throated mountain blackbird (Ring Ouzel), glimpsed fleetingly amongst the mossy crags (Bewick refers to it as the Rock Ouzel); of hearing the deep, throaty kraa call of that eponymous mountain bird, the Raven; encountering the harsh, chack-chack of Fieldfare on grey, bleak, overcast, crepuscular wintery ascents via Red Tarn or the air-filled, spring-joy of the skylark’s song on the grassy whaleback ridge that runs from Whiteside over Helvelyn down to Grisedale Tarn:

… Left hand, off land, I hear the lark ascend,

His rash-fresh re-winded new-skeinèd score

In crisps of curl off wild winch whirl, and pour

And pelt music, till none ‘s to spill nor spend …

Gerard Manley Hopkins[12]

---------------------------

In his essay for Walking Poets, Dr Kaz Oishi (in Collier 2015)[13] suggests that Wordsworth’s poems on his Scottish tours ‘are comparable to Basho’s journey to the North’ outlined in Oku no Hosomichi, both recounting ‘pilgrimages to literary and historic sites’ … journeys filled with what Wordsworth called ‘Spots of Time’- ‘moments of self examination upon encountering sites of literary and collective memories’. I have myself followed in Basho’s footsteps in Japan on two separate visits – and at Mount Nikko experienced such moments.

Oishi’s comparison was extended by writer-artists Alec Finlay and Ken Cockburn who in 2011 completed The Road North ‘a project inspired by the 17th-century Japanese pilgrim-poet Matsuo Bashō, who perfected the haibun form of prose-poetry as a means of recording the thousands of miles he wandered through Japan. Guided by the example of Bashō, Finlay and Cockburn followed their own narrow roads through Scotland, stopping at fifty-three "stations" and creating a "word-map" of the country, made up of prose-poems, renga, hokku and blog posts. This project was exhibited in Walk On: Forty years of Art Walking – Richard Long to Janet Cardiff, co-curated by myself, Cynthia Morrison Bell and Alistair Robinson in 2013.

I included a number of other artists in this show whose work could be described as ‘about pilgrimage’ in some form, including the map-maker and writer Tim Robinson. Robinson is the alter ego of (former) artist Timothy Drever whose abstract paintings and environmental installations were seen in a number of exhibitions in London before he moved to the west of Ireland in 1972. For Walk On, I selected pages from his book Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage (1990) shown alongside Oilerin Arann – a hand drawn map of the Arann Islands, Co. Galway, Eire. (1996)[14]. The map and accompanying text were beautifully drawn and meticulously researched, explaining the derivation and meaning of hundreds of place names and representing a wide range of information about the region’s culture and landscapes. Robinson has gained much of this information literally on the ground, walking with naturalists, historians, archaeologists and other specialist through the landscape. His maps and books provide an invaluable guide for visitors to the region as well as nourishing community spirit by identifying the irreplaceable uniqueness of the local environment and history.

---------------------------

I first came across the work of Robinson whilst on a visit to the West Coast of Ireland in 1999. Knowing of my keen interest in walking, friends in Galway suggested I might like to climb Croagh Patrick (“Croagh” comes from the Irish cruach, meaning “mound”) – ‘Ireland’s holiest mountain and reputedly a place of pilgrimage for more than fifteen hundred years’. Known locally as the Reek (from the word “rick”, as in “stack”), ‘Croagh Patrick rises from the southern edge of Clew Bay near the town of Westport”. William Thackery Makepeace wrote in his Irish Sketch Book (1843) “ … it is clothed in the most magnificent violet-colour, and a couple of round clouds were exploding as it were from the summit, that part of them toward the sea lighted up with the most delicate gold and rose colour.”[15]

Legend has it that in 441, St Patrick spent the forty days and nights of Lent fasting on its peak. Every year, up to 100,00 pilgrims climb the Reek and Masses are held at the summit (at 2,500 feet) on Reek Sunday (the last Sunday in July) where there is a small chapel. Some carry out what are called ‘rounding rituals’, which were formerly a key part of the pilgrimage. This involves praying while walking sun-wise around features on the mountain; seven times around the cairn of Leacht Benáin (Benan’s grave); fifteen times around the circular perimeter of the summit; seven times around Leaba Phádraig (Patrick's bed), and then seven times around three ancient cairns known as Reilig Mhuire (Mary's cemetery).

My ascent took place on Saturday the 24th of July 1999 – a day before the annual pilgrimage, although a considerable number of pilgrims, unable to make it the following day, were walking up Croagh Patrick that July Saturday. I chatted to many people on the way up – the pilgrimage is a social as well as religious event – and the oldest person I met was over eighty years old. The ascent begins easily enough but towards to top, the path steepens considerably and the going becomes rougher as the route to the summit takes pilgrims over stretches of shale. The view from the top is airily extensive; to the south, the green plains of Mayo open up, with the sharp-peaked quartzite hills of the Twelve Bens or Twelve Pins (Irish: Na Beanna Beola) and the Maumturks range in Connemara in the far distance; to the north, the jewelled islets of Clew Bay sparkle (there are said to be one for every day of the year). I found the experience moving; the rhythmic pace of my feet (the climb is not technical) encouraging meditation. Indeed, the ‘Croagh Patrick Pilgrimage is as much about traveling as it is about arriving. It is a pilgrimage in which the natural elements – the mists and unexpected vistas of sea and distant hills, the sudden changes from clear blue skies to monotonous grey rain, the spontaneous words of encouragement passed like batons of friendship between pilgrims – all contribute to a sense of the pilgrim experience of communitas, a feeling of participating together in an exhilarating spiritual enterprise.’[16] (Harpur 2016)

---------------------------

Although I do sometimes walk on my own, my research is more usually ‘conducted’ through conversive art walks (usually slow meanders) which are inclusive, involving artists, natural and social historians, poets, sound artists as well as students and the public. These walks encourage participants to experience the world with the heart and through all their senses. On my walks, participants gather and share the knowledge that comes directly from experience (from the wildness of the world) – a process called biognosis – meaning knowledge from life; research and knowledge which I hope encourages people to care more about their environment and therefore to effect positive change.

I would describe a number of these walks as secular ‘pilgrimages’. For example, ‘In Temperley’s Tread - the Birdlife of Durham's Moor and Vale’ comprised a suite of upland bird and wildlife walks, staged through Durham’s upland landscape along a historic route. Walking with thirty members of the public over five days in the summer of 2012, and led by natural historian Keith Bowey, we journeyed in George W. Temperley's footsteps following a route suggested in the introduction to A History of the Birds of Durham (Temperley 1951)[17]. Extolling the virtues of County Durham’s western area, he said:

To realise the extent of these far-flung moorlands the traveller, who only knows the industrialised portions of the County in the east, should walk from Edmundbyers on the Derwent through Stanhope in Weardale to Middleton in Teesdale, returning by Langdon Beck, St. John’s Chapel, Boltsburn, Hunstanworth and Blanchland, a circuit of some 45 miles. In the course of such a walk the only signs of cultivation which meet the eye are restricted to the narrow strips along the river banks and the only traces of industry are the relics of long disused lead mines and quarries.

It should be remembered that whilst much of this bleak landscape falls within the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the ecology of the area is partially the result of lead-mining and limestone quarrying on an industrial scale in the Dales during the eighteenth and nineteenth-century. Throughout this five-day walk, I took notes of the things seen and heard and then used these notes to create a series of new work back in my studio.

Five walks; Five Birds of the Durham Uplands (In Temperley’s Tread)

Gog (Cukcoo); Riphook (Merlin); Lypwingle (Lapwing); Pynot (Oyster Catcher); Courlie (Curlew) - Letters taken from George Temperley’s type written manuscripts.

Digital print (one of ten); 2013. 25 x 83 cm

‘June and early July 2012 saw unprecedented falls of rain and unseasonably chilly weather. However, on the day of our first walk, from Edmunbyers to Stanhope, the weather broke and we had sunshine and gentle, warm winds for most of an excellent day’s walking. The highlights included: Cuckoo, Oystercatcher, Common Sandpiper, Short-eared Owl, Curlew, a couple of families of Wheatear, Redshank, Lapwing, Snipe (including the extraordinary sound of four Snipe ‘drumming’ around us on top of the moors), Ring Ouzel, Golden Plover, Buzzard, Red Kite and Kestrel (and, of course, many Red Grouse and Meadow Pipits).

Watching Snipe ‘drumming’ in the Durham (In Temperley’s Tread, July 2013)

On walk two, from Stanhope to Middleton-on-Tees, the weather was showery with broken spells of blustery sunshine. We walked high across largely trackless, heather moors – an invigorating experience, ‘though tough walking! We saw most of the birds seen on walk one although in smaller numbers in the case of the waders; clearly, having bred successfully (hopefully), they had begun to leave the high moorlands. We also saw a family of Stonechat and, the highlight of the day, two Merlin and a Hobby – at the same time.

Watching Lapwing in the Durham Uplands (In Temperley’s Tread, 2013)

Lymptwigg: Lapwing (In Temperley’s Tread)

Digital print (one of ten); 2012

35 x 77 cm

On walk three, from Middleton-on-Tees to St John’s Chapel our route took us, initially, along the banks of Tees as far as the Wynch Bridge. This stretch of the river is internationally renowned for its wealth of flora and we saw an abundance of wildflowers in the uncut hay meadows and on the valley floor, including Wild Pansy, Hay Rattle, Globe Flower, Lady’s Mantle, Pignut and Oxeye Daisy as well as Heath Milkwort on the riverbank at Low Force. We left the Tees at Newbiggin, climbing steadily along an unclassified road until we reached the highest point on our walk, Swinhope Head (at just over 600 metres). As the afternoon progressed and we made our way over Green Fell and Pike Law, the wind grew in strength, keeping many of the birds down. We had a fleeting view of a Merlin as it flew along the flanks of Black Hill, but by the time we reached journey’s end at St. John’s Chapel, the wind had reached gale-force. However, we did manage to see a total of six different bedstraws on this walk – Heath Bedstraw; Marsh Bedstraw; Northern Bedstraw; Cleavers; Crosswort and Lady’s Bedstraw.

Walk four (a much shorter walk of around seven miles) began at St. John’s of Warden Hill. From here, we climbed Cuthbert’s Heights where we saw a Black Grouse on Northgate Fell and caught site of a Peregrine in the distance over the North Durham Fells. Perhaps the highlight of this walk was seeing juvenile Redstart and

The Stanhope Burn; from George Temperley’s Journal, June 4th 1933

Unison Pastel onto Digital Print; 2013

34 x 42 cm

Crossbill at the edge of a small conifer plantation on Hangingwells Common. Our route then took us across Smailsburn Common and, as we made our way into Rookhope, we encountered many Common Spotted Orchids, Ragged Robin, Teasel, Wild Thyme and a range of grasses.

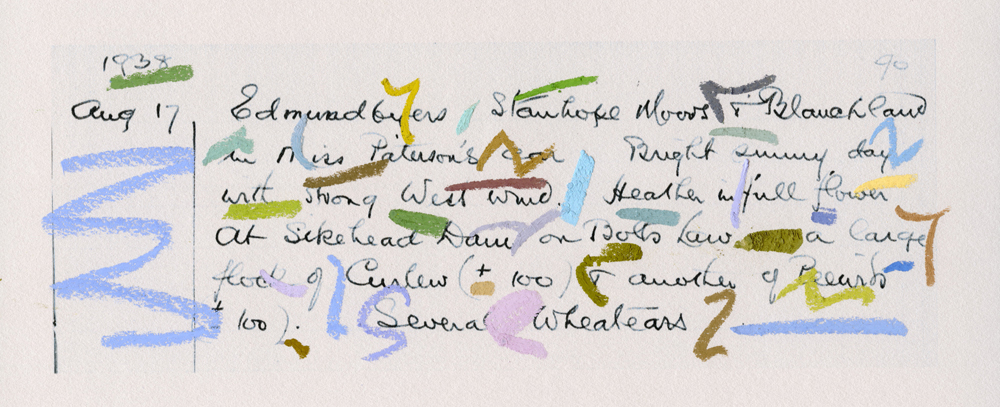

Edmundbyers, Stanhope Moors and Blanchland;

From George Temperley’s Journal, August 17 1938

Unison Pastel onto Digital Print; 2013

28 x 42 cm

Walk five took us from Rookhope to Blanchland via Bolt’s Law – a terrific view point. From its summit (540m), we could see over to the Cheviots, Simonside, The Pennines as well as Newcastle and Sunderland. Many of the waders had now left the uplands – there were small numbers of Golden Plover, Lapwing and Curlew, but the really exciting sighting was of a Raven. Ravens no longer breed in Co. Durham and are rare, having been persecuted to near extinction’.

---------------------------

Concluding reflections:

For me, pilgrimage is about embarking on a journey of discovery that takes me out of myself; it is not an inward looking process. I often walk in the footsteps of others and usually with natural historians, sound artists, photographers and local people - because they have different things to tell me about the landscape we meander through. And meander is the correct term to use for this slow walking. I allow plenty of time to stop, talk, listen, backtrack, share memories and slow down, and indeed I do see my meanders as part of the slow-living philosophy.

Learock: Skylark (In Temperley’s Tread)

A collaboration with Tim Collier

Digital print; 2013

68 x 84 cm

Parkins and Craig (2006) situate the concept of ‘slow living’ within a larger cultural reaction to the time/space dislocations and the disjunctures of globalization. Slow living, they argue, can be understood as an attempt to ‘individualize’ and to challenge normative trajectories of global capitalism. It is “fundamentally … an attempt to exercise agency over the pace of everyday life”[18]

Most of my walks or pilgrimages are relatively local and have some sort of personal significance, however, I do not see them as a retreat into parochialism; quite the opposite; we live within, and not outside, a global market economy - a series of complex, interrelated local economies. If we are to successfully negotiate this apparent deterritorialization of culture, we need to understand our posthumanistic sense of place and individuality (Danby and Hannam 2017)[19]. To do this, we need to challenge dominant forms of contemporary thinking and at times to reinvent it. This requires us to confront hierarchical, normative ways of looking at the world. It also requires creative and syncretic thinking – something that meandering pilgrimages give us the space to do. These conversive pilgrimages develop creative, non-hierarchical, rhizomatic networks of shared thinking and ideas. They make us feel more alive; more a part of the world in every sense and not separate from it; a celebration of the joy of being.

[1] WALK (Walking, Art, Landskip and Knowledge) is a research centre at the University of Sunderland exploring the way we creatively experience the world as we walk through it.

[2] MacFarlane, R. (2012) The Old Ways. London: Hamish Hamilton.

[3] Wylie, J. (2007) Landscape, London: Routledge.

[4] Ingold, T. (2000) The Perception of Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill, London:

Routledge.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Parkins, W. and Craig, G. (2006) Slow Living. Oxford: Berg.

[7] Henry David Thoreau (2017), Walking. Thomaston, Tilbury House Publishers.

[8] Collier, M. (2014) Wordsworth and Bashō: Walking Poets. Sunderland and Grasmere: AEN and the Wordsworth Trust.

[9] Hanley, K. (2013) ‘The Imaginative Visitor: Wordsworth and the Romantic Construction of Literary Tourism in the Lake District’ in Walton, J. K. and Wood, J. (eds.) The Making of a Cultural Landscape – The English Lake District as Tourist Destination, 1750–2010, Farnham: Ashgate.

[10] Derbyshire, H (ed) 1958 The Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth, Oxford, OUP.

[11] ‘To -[Miss Blackett], on Her First Ascent to the Summit of Helvellyn’, William Wordsworth.

[12] ‘The Sea and the Skylark’, Gerard Manley Hopkins.

[13] Oishi, K. ‘Two Recollective Journeys to the North: Bashō and Wordsworth’ in Collier, M. (2014) Wordsworth and Bashō: Walking Poets. (Sunderland and Grasmere: AEN and the Wordsworth Trust, 2014),

[14] Robinson, T (1990). Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage. London, Penguin.

[15] Harpur, J. (2016) The Pilgrim Journey: A History of Pilgrimage in the Western World. Oxford: Lion Books

[16] Ibid.

[17] Temperley, G (1951) in ‘A History of the Birds of Durham’ as Vol. IX of the Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

[18] Parkins, W. and Craig, G. (2006) Slow Living. Oxford: Berg.

[19] Danby, P. and Hannam, K. In Entrainment: Human-Equine Liesure Mobilities. Rickly, J. (Ed.), Mostafanezhad, M. (Ed.), Hannam, K. (Eds). (2017) Tourism and Leisure Mobilities. London: Routledge.