If we think about the evolution and history of mobility in time and space, we could easily find a practice that has essentially never changed: the practice of walking. We changed our itineraries, the necessity to walk, the surroundings, the features and characteristics of the streets, the tracks and pathways, the quality and shape of the shoes we use (or not) to walk, but the way we move one step after the other has remained similar throughout the long history of humankind.

In the current social ecosystem – the one that produces every year over 70 million cars,[1] and the one where the new “flying planet”, with over 11 million persons in the air every day,[2] grows relentlessly – walking stands as an increasingly necessary practice and mind-set.

Walking constitutes more than ever a very important methodology that allows an inspiring convergence between theory and practice, revealing an interesting dialogue and interchange between art, architecture, urban studies, sustainability, ecology and technology. Walking, with a holistic perspective, discloses the multiple layers of experience in the relationship between people and places. As stated by Rebecca Solnit: “Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned (…)”.[3]

There are many interpretations and ways of understanding it, but walking is definitely not only about moving our feet in one direction. The practice of walking has been addressed by many authors, who analysed its multiple concepts and meanings through different perspectives: through an historical standpoint (Solnit, 2000), as a philosophy (Grós, 2011), as a socially engaged practice (Pujol, 2018), as an aesthetic experience (Careri, 2006) or as a spiritual one (Thich Nhat Hanh, 2015), among others. Walking is meditation and mindfulness. Walking is slowness and a way of travelling at a different pace. Walking is a tool for exploration and analysis. Walking is undeniably a natural engine and fuel that nurture our body and mind, a metaphor of our constant tension between standing and moving: one foot on the ground, the other one flying in the air, generating a constant balance between earth and sky, between past and future, between roots and innovation, between where we come from and where we are heading to.

Many thinkers and philosophers have considered walking as an essential tool for thinking. Friedrich Nietzsche asserted that: “All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking”,[4] while Jean-Jacques Rousseau declared about himself that: “I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind works only with my legs”.[5] This intimate relationship between thinking and walking is also underlined by Solnit, who remarked that: “The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passage through a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series of thoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage, one that suggests that the mind is also a landscape of sorts and that walking is one way to traverse it. A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along, as though thinking were traveling rather than making”.[6]

The connection between walking and thinking is not only a clear and strong philosophical statement, but is also recognized in scientific evidence.[7]

Walking Art

Walking practices have been and are being used by many artists in order to discover and explore a specific territory, city and geography; or to pursue an experience of having both the body and mind aware of the place they occupy and, simultaneously, aware of their process of being-in-mobility. Walking practices are also used as a strategy to address geopolitical, social, economic or environmental issues and to question territorial and political configurations. There are multiple dimensions of walking art experiences: from collective walking practices and local exploration, to spiritual walks in search of the self; from the political use of walking, to the introduction of technology; from a poetical subtle act, to environmental activism; from the solitary and personal action, to its function as a tool for participatory practices; from its employment as a methodology, to its understanding as an attitude.

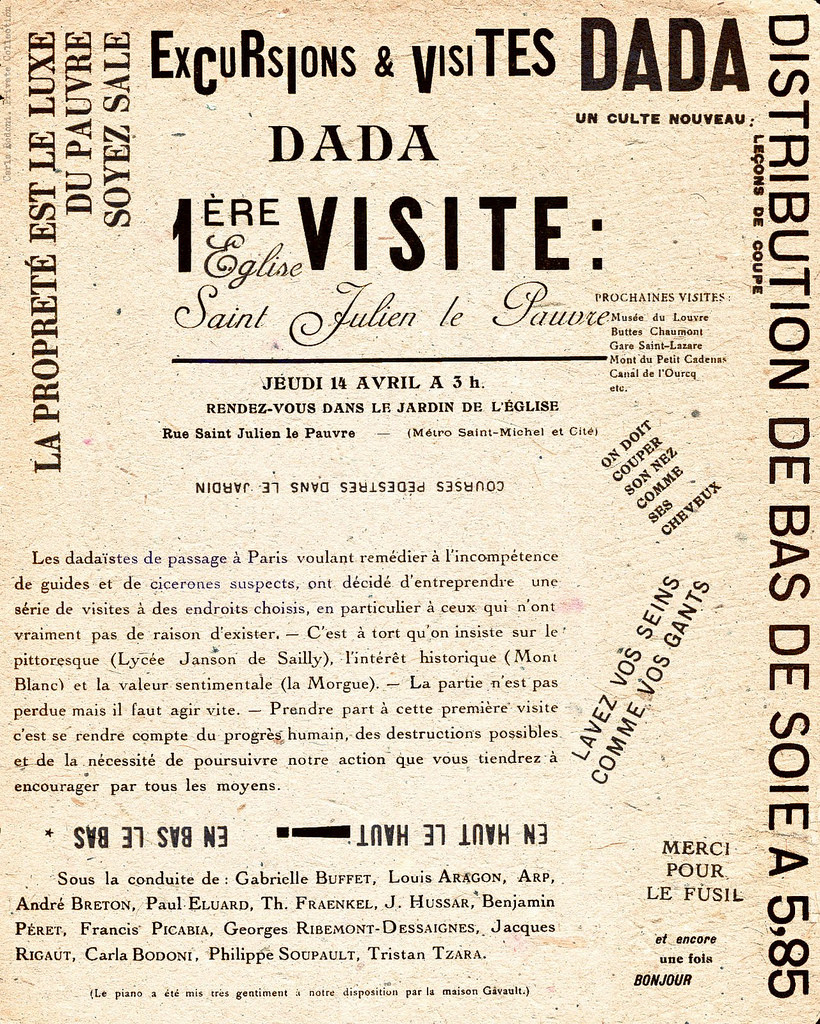

DADA, "Excursions & Visites" Manifesto, 1921

One of the first walking performances in the history of art was realized by a group of DADA members on April 14, 1921. Through the manifesto “Excursions and Visites” – signed by Gabrielle Buffet, Louis Aragon, Arp, André Breton, Paul Eluard, Théodor Fraenkel, J. Hussar, Benjamin Péret, Francis Picabia, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Jacques Rigaut, Philippe Soupault and Tristan Tzara – the group advertised a series of excursions to “places that have no reason to exist.” We could say that it was a kind of anti-touristic walk. They finally did just one – to the church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre in Paris – that was to some extent a failure. During the walk they were reading poetry and performing a parody of a tour guide, but other actions were cancelled due to rain, other people and an orchestra that never showed up.

Dada excursion to Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, Paris. 14 April 1921.

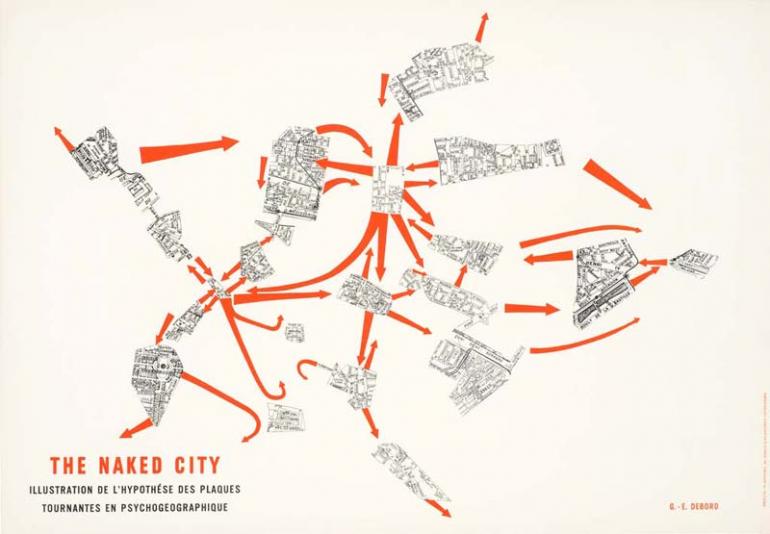

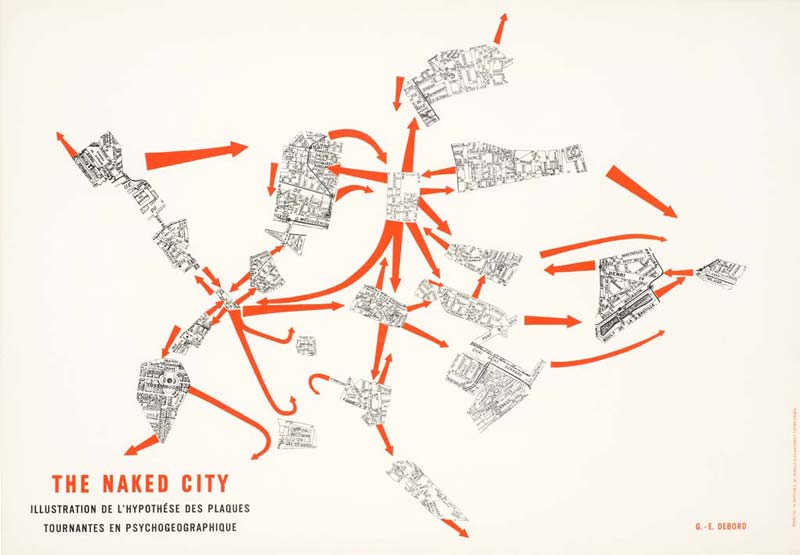

Another peculiar way to discover the city was offered by Guy Debord. The philosopher and founding member of the Situationist International created maps with psychogeographics contours and proposed to explore the city through the practice of the dérive (or drift). In the Theory of the Dérive (1956), Debord describes: “One of the basic situationist practices is the dérive, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. (…) from a dérive point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.”[8] The unconventional methodology of the dérive - a mix between awareness and letting-go – soon became an exciting approach and tool for artists, architects and urban explorers who exploited the creative potential of it. The city became a living organism, a sum of pulsating veins, breathing boundaries, attractive zones and disorienting confluences worth walking and experiencing.

Guy Debord, The naked city, 1957.

Walking is also a way to get out of the city; a way to deal with, respect and connect to nature; a method to explore the limits and parameters of landscape; a mode through which to question, challenge or emphasize the climatic, atmospheric and environmental phenomena.

The famous example of A Line made by Walking, by Richard Long in 1967, suggests a poetical alteration of landscape by walking. This piece is particularly relevant because it places itself in the narrow space between performance and sculpture. The artist leaves his corporeal presence on the land through the main action of walking. Most of the art pieces realized by Long – sculptures, drawings and textworks - are related to walking and the artist himself wrote extensively about this topic, affirming that: “Walking – as art – provided a simple way for me to explore relationships between time, distance, geography and measurement”.[9]

Another British artist who belongs to the same generation of Long, and who has always defined himself as a “walking artist”, is Hamish Fulton. Since 1973 Fulton has only made works based on the practice of walking, essentially focused on the experience itself, without any intention of leaving traces in the landscape. Fulton seeks a poetical and careful approach, which somehow refuses the system of art and the materiality of artworks in search of a path towards freedom. He claimed that “An artwork may be purchased, but a walk cannot be sold”,[10] and in talking about the origin of his practice, affirmed that: “There was no influence really coming from history. My practice is more related to a sense of freedom from society to break down what art is supposed to be”.[11]

Hamish Fulton, Caminata en Riaño – Fundación Cerezales, 2017. Photos: Jean Marc Manson. © Hamish Fulton

Walking is often used as a methodology to create awareness about the ecological glocal situation and express support in favor of environmental concerns. Some of the performances by Jess Allen – who defines herself as a Tracktivist,[12] and uses walking art as an eco-activist performance in rural landscapes – are related to this specific aspect of creative walking practices.

Other projects like the Windwalks, by Tim Knowles, the film 0º00 Navigation Part I: A Journey Across England or the trilogy Going Nowhere by Simon Faithfull, reveal an interesting walking approach where the configurations of the planet, its limits and natural phenomena (wind, snow, water, tides or the Greenwich Meridian) guide, influence and inspire the creative directions.

Simon Faithfull, Going Nowhere 1.5, HD video, 9min, 2016. GoingNowhere_1pt5 from Simon Faithfull on Vimeo.

Walking in the open field is also a practice often used by Simon Pope, an artist with a consistent body of work developed through, and about, walking. Nature and ecology – in Pope’s practice – are just some of the possible approaches where walking becomes a tool to analyze creative practice and generate dialogue, relationships and participatory processes. Memories, as well as cultural, social and political questions, arise from the multiple walking conversations realized by Simon Pope for his projects (e.g. Memory Marathon; From Unspoken Landscapes; The Long Walk Home; The Memorial Walks; among many others).

Paying attention to the political and social aspects of contemporary society is also at the forefront of the walking artists. Francis Alÿs, a Belgian artist based in Mexico City since the eighties, has often used walking as a tool to unveil, question and reflect upon the many human and political paradoxes and conundrums in diverse territories and societies. Different works, like The Collector, Re-enactments, The Leak, The Modern Procession, The Green Line, among others, all contain specific actions and situations related to the walking practice. In his understanding and intentions: “Walking is not a medium, it’s an attitude. It favours inspiration, it is conducive to the development of ideas, and it is also highly accessible”.[13]

The specificity of a territory, with all its contradictions, local conflicts and constant transformations, also constitutes a research angle within the socio-political approach of the walking practice. We Walk Lahore is a project developed by Honi Ryan comprising a series of actions, performances and research aimed at exploring the complexity of a city where walking seems to be a denied ritual. As the artist argues “there are a multitude of factors that can make it uncomfortable to walk the streets of Lahore: social, environmental and architectural to name a few”.[14] The actions developed by Ryan in Lahore aimed to activate awareness in order to foster a new encounter between the city and its citizens. The creative analysis of this “lost encounter” between the city and the citizens – due to a growing series of restrictions, limits and material and immaterial boundaries – and the will to regain this meeting space, thereby creating an open sense of accessibility and new connections between people and places, are likewise addressed in the walking/dancing project Urban Chaari by Manishikha, in Delhi,[15] or in the nocturnal walk of the project Crossing Jericho by Susanne Bosch, in Palestine.[16]

Honi Ryan. Walking Presence. 2016. Photo by Kashif Saleem.

Other artists have introduced the use of technology in the development of their walking art projects. The audio-visual dimension, as used in several works realized by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, opens up parallel realities that complement the physical experience of walking. An interesting example is the video walk project Alter Banhof, produced for d(OCUMENTA) 13 in Kassel. The participants, equipped with headphones and following the video put on an iPod, were guided through the old train station of the German city. The project generated the coexistence of a double reality: the one in the video and the one in real time.

Another project worth mentioning is the Electrical Walks that Christina Kubisch started, as a work in progress, in 2004. As the artist describes: “[The Electrical Walks] is a public walk with special, sensitive wireless headphones by which the acoustic qualities of aboveground and underground electromagnetic fields become amplified and audible”.[17] The experiments with sound, music and urban noises show other passageways and directions to explore the cities and know their more hidden corners.

Alter Bahnhof Video Walk; 2012; Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller from Cardiff & Miller on Vimeo.

As a final example I would like to mention two more projects that can be related to walking from a very different position, that of standing in-between walkers. The performance The Encounter, organized by the Albanian artist Adrian Paci, deals with a positive metaphor of the Mediterranean: the metaphor of the encounter. The artist stands in the central square of San Bartolomeo in Scicli, a town in Sicily, and a long line of several hundred people walks towards him with the objective of shaking his hand. The location, and the entire island of Sicily, is symbolic of the passages of different people and cultures in this land across history; and the performance represents the will to re-establish an ideal place where different identities meet and share a new encounter.

Furthermore, the act of “walking towards the other” makes us think about the multiple experiences related to migration, about the feeling of belonging in the complex processes of relocation and about regrounding. According to Anne Ring Petersen, the migration experience “involves a multi-layered and multi-territorial process of losing one’s sense of feeling “at home” in one place and, in most cases, regaining a sense of personal, social and political belonging elsewhere through an ongoing process of “regrounding” or “getting-back –into place””. [18]

Simultaneously strong and fragile, A Needle Woman, a performance video artwork by Kimsooja, represents the artist standing in the most crowded streets of several world megacities (London, Shanghai, Tokyo, New York, Mexico City, Cairo, Lagos, Delhi, to name a few). A relentless flow of a walking humanity steps in all directions, while the artist stands firm in-between the multitude, somehow representing a moment of peaceful pause, a moment of suspension before embarking again in the infinite journey of the human being.

Kimsooja, A Needle Woman, 1999 - 2001, eight channel video projection, 6:33 loop, silent, Courtesy of Kimsooja Studio

Beyond all the mentioned artworks and walking artists, it is important to affirm that there is definitely a growing interest in this practice and its contemporary echoes, reflections and thoughts with regards to the values, relevance and meanings that it conveys.

A very diverse range of projects revolves around the topic of walking, such as: walking residencies;[19] university research projects;[20] participatory performances and workshops;[21] a walking institute;[22] a museum of walking;[23] a walking artists network;[24] as well as an increasing translation of these practices into exhibitions and multidisciplinary events.

Conclusions

In order to conclude, we could definitely affirm that walking is not a new practice to discover, but that it has been somewhat neglected and it is currently marginalized by the life style proclamations of the modern world. Metaphorically, we could say that the act of walking therefore means reclaiming a different and more balanced ecosystem. The choice to develop walking art practices responds nowadays not only to a specific media or methodology to create artistic content, but is first and foremost an attitude, a stance, a message and a value. In that sense: What would be the messages and values of a walking practice in the 21st century? Where does the walking practice stand in the relentless evolution of technology and mobility? How can contemporary art contribute to the re-discovery of the walking practice with new strategies, visions and methods?

Walking practices and their manifestation in art, architecture, urbanism, technology and other disciplines and creative media, pave the way to a new sustainable environment, which we should all aim for as soon as possible. Walking, as described by several artists and thinkers mentioned above, constitutes a path towards freedom, a tool to reconnect with the lost interaction with nature, a liberation from modern schizophrenia. Walking as a way of liberation can be interpreted, somehow, as a way to escape the pressure of the ego. As Frédéric Gros articulated: “By walking, you escape from the very idea of identity, the temptation to be someone, to have a name and a history. (…) The freedom in walking lies in not being anyone; for the walking body has no history, it is just an eddy in the stream of immemorial life”.[25]

In-between the multiple pathways, routes and journeys carried out by a growing multitude of people in transit, it is highly interesting to focus, explore and decipher the subtle, creative and mindful space between one step and another.

Bibliography

- Guy Debord, The Theory of the Dérive, 1956

- Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking. Verso. London, 2011.

- Anne Ring Petersen, Migration into art. Transcultural identities and art-making in a globalised world. Manchester University Press, 2017.

- Marily Oppezzo and Daniel L. Schwartz, Give Your Ideas Some Legs: The Positive Effect of Walking on Creative Thinking, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 2014, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1142–1152.

- Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin Books, 2001.

- Honi Ryan, “We Walk Lahore”, in: Urbanities. Art and Public Space in Pakistan. Edited by Sara-Duana Meyer and Stefan Winkler. Goethe-Institut Pakistan, 2017.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions, Book IV. 1903.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the idols, or how to philosophize with a hammer. Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von C. G. Naumann. Aphorism 34. 1889.

- Francesco Careri, Walkscapes. Walking as an Aesthetic Practice. Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2008.

- Ernesto Pujol, Walking Art Practice: Reflections on Socially Engaged Paths. Triarchy Press Ltd, 2018.

- Thich Nhat Hanh, How to Walk, Parallax Press, 2015.

[1] Available at: <http://www.worldometers.info/cars/> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[2] Estimated from data found on: Hugh Morris, “How many planes are there in the world right now?”, The Telegraph, 16 August 2017. Available at: <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/travel-truths/how-many-planes-are-there-in-the-world/> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[3] Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin Books, 2001. Page 2.

[4] Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the idols, or how to philosophize with a hammer. Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von C. G. Naumann. Aphorism 34. 1889.

[5] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions, Book IV. 1903. Available at: <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3913/3913-h/3913-h.htm#link2H_4_0005> [Accessed 20 October 2018]. In its first English translation, this sentence reads: “Walking animates and enlivens my spirits; I can hardly think when in a state of inactivity; my body must be exercised to make my judgment active”.

[6] Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin Books, 2001. Page 3.

[7] Check the research report: Marily Oppezzo and Daniel L. Schwartz, Give Your Ideas Some Legs: The Positive Effect of Walking on Creative Thinking, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 2014, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1142–1152. Available at: <https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/xlm-a0036577.pdf> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[8] Guy Debord, The Theory of the Dérive, 1956. Page 1. Source: UbuWeb | UbuWeb Papers. Available at: <http://tbook.constantvzw.org/wp-content/derivedebord.pdf> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[9] Richard Long: Heaven and Earth. TATE. Available at:

<https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/richard-long-heaven-and-earth/richard-long-heaven-and-earth-1> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[10] Hamish Fulton website. Available at: <http://www.hamish-fulton.com> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[11] Esperanza Collado, “Hamish Fulton: Walking On and Off the Path”, in: Concreta. Available at: <http://www.editorialconcreta.org/Hamish-Fulton-Walking-On-and-Off-355> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[12] The term Tracktivism means, in Jess Allen’s words: “walking along tracks with activist intent: an emerging field of eco-activist performance that synthesises the practices of walking art and one-to-one performance in (predominantly) rural landscapes”. Check in this issue: <https://walkingart.interartive.org/2018/11/Tracktivism>

[13] Francis Alÿs. “Walking distance from the studio”. MACBA, 2005. Available at: <https://www.macba.cat/en/exhibition-francis-als> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[14] Honi Ryan, “We Walk Lahore”, in: Urbanities. Art and Public Space in Pakistan. Edited by Sara-Duana Meyer and Stefan Winkler. Goethe-Institut Pakistan, 2017. Page 11. Check in this issue:

<https://walkingart.interartive.org/2018/12/Walking-presence-honi-ryan>

[15] Manishikha Baul, Urban Chaari. Check in this issue: <https://walkingart.interartive.org/2018/12/manishikha>

[16] Susanne Bosch, Walking as Relational Aesthetics. Check in this issue: <https://walkingart.interartive.org/2018/12/susanne-bosch>

[17] Christina Kubisch, Electrical Walks. Available at: <http://www.christinakubisch.de/en/works/electrical_walks> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[18] Anne Ring Petersen, Migration into art. Transcultural identities and art-making in a globalised world. Manchester University Press, 2017. Page 9.

[19] Some of the most recent projects include: Wonder, Wander, a collective walking residency in Jordan organized by Spring Sessions; the Walk & Talk Residencies organized by Arc in Switzerland; the Caribic Walking Residency; the Walking the City programme in the framework of Metropolis, Art and Public Space in Copenhagen; or the Grand Tour organized by Nau Côclea in Spain, to name a few.

[20] Check the research center W.A.L.K. (Walking, Art, Landskip, and Knowledge). University of Sunderland. Available at: <https://walk.uk.net> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[21] I would like to mention here two personal projects developed in 2017 and 2018: the performance Love is Walking Together (November 2017), organized in collaboration with Jakob & Manila Bartnik, part of the Third Staging Post of the international project CAPP (Collaborative Arts Partnership Programme) at the Kunsthalle Osnabrück; the workshop Walking Practices: Entering the Woods, organized in the Grunewald Forest (Berlin, 2018) as part of the Transart Summer Residency.

[22] Available at: <https://www.deveron-projects.com/the-walking-institute/> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[23] Available at: <http://www.museumofwalking.org/info/> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[24] Available at: <http://www.walkingartistsnetwork.org> [Accessed 20 October 2018].

[25] Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking. Verso. London, 2011. P. 6-7.