I. In his 2014 book A Philosophy of Walking, Frédéric Gros looks to ancient Greece to outline two distinct forms of walking: contemplative and cynical. Contemplative walking, he claims, evolved from Aristotle’s Lyceum and the Peripatetic School of Philosophy [1]. Peripatetic roughly translates to “of walking” and, as art historian Lexi Lee Sulivan has pointed out, this early interest in walking while thinking gave rise to “rich philosophical and literary traditions” [2]. In short, contemplative walkers have historically been cultural producers. For them, walking is a means of contributing to society. Alternatively, Gros traces cynical walking to the nomadic Cynics who roamed ancient Greece searching for elemental truth outside of society. Sullivan summarizes:

Having given up their possessions, the Cynics were a disaffected, homeless populace ambling from place to place barking in opposition to convention … Cynics walked in resistance to the status quo and as such established walking as a countercultural activity [3].

Gros uses these two types of walkers to lay the groundwork for what he refers to as the modern flâneur, the urban stroller who fails to take part in the economic activities of the city – a perfect composite contemplative-cynic. In this essay, I propose that British walking artist Hamish Fulton also operates in this middle ground between contemplative and cynical walking. However, unlike the flâneur, Fulton is not a perfect composite.

As I will show, there is an inherent tension between Fulton the subversive walker and Fulton the exhibition artist. To illustrate this point, I will focus on two case studies that expose these distinct and oppositional sides of Fulton’s practice. The first, 21 Days in the Cairngorms (2010), illustrates a culturally productive gesture towards a sustained and widespread culture of walking. The second, A Guided Mountaineering Expedition to the Summit of Denali (2004), shows the artist indulging in pure cynicism, directly responding in opposition to the so-called land artists. For Fulton, each of these walks is a work of art in and of itself, but it is unclear what exactly he claims to create. What does his walking produce? And how might the success of one walk be compared to another? If we consider Fulton a contemplative walker, the productivity of his walk stems from its capacity to be translated into cultural capital and intellectual development. If we consider him a cynical walker, his walks can no longer be valued for the impact they produce, but for their capacity to undermine, destroy, or escape the civilizing forces that obscure universal truths. Fulton’s walking practice is pulled between these two sides. He idolizes the subversive nomad who ceaselessly wanders out of bounds, but never fully exorcises his walks from the realm of productive contemplation. In this sense, Fulton’s walks theatrically display a negotiation of his identity as an autonomous, countercultural walker who inevitably succumbs to the role of culturally conscious producer.

II. In 1964, an 18-year-old Hamish Fulton began studying sculpture at Hammersmith College of Art in London. Five years later, he would fail out of the Royal Academy of Art and explicitly reject his identification as a sculptor before flying to the American Great Plains Region and declaring himself a “Walking Artist.” Throughout his long and prolific career he has continued to defend this distinction between his work and sculpture, however, his staunch rejection has only spurred scholars to read his work through this lens. Ironically, without Fulton’s outspoken dismissal, his connection to sculpture is not immediately apparent. His work tends to be experienced as text and image-based publications as well as gallery installations featuring flat, graphic wall paintings and framed prints that read like concrete poems.

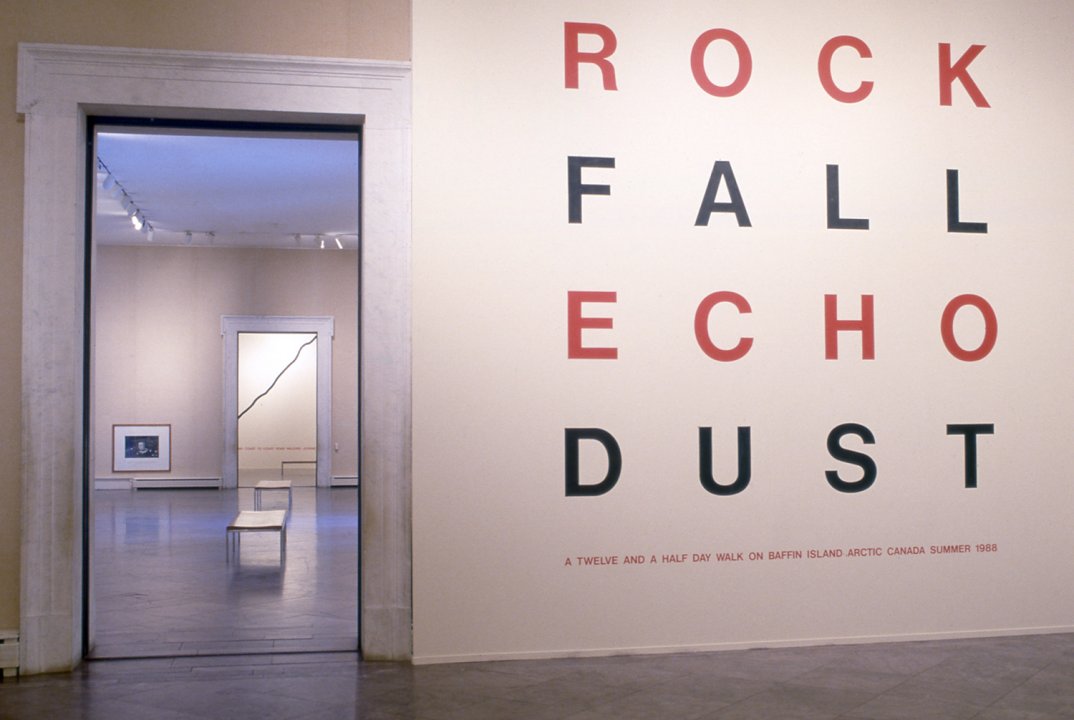

Installation view of Hamish Fulton: Selected Walks, 1969–1989. Photograph by Tom Loonan

In general, his work is wall or book bound, unable to be experienced in the round, and without the sense of objecthood or provenance granted most sculpture. Over the past five decades, his exhibitions have generally become more site-specific and immersive, but he has rarely produced objects that readily read as sculpture. And yet, Fulton’s work is indebted to sculpture.

This debt becomes apparent in Sullivan’s history of walking as art, which for her begins with early twentieth-century Dada. As Sullivan states:

Born out of the First World War, Dada was a geographically diverse artistic expression that rejected conventions and employed unorthodox anti-rationalist techniques that questioned the boundaries between art and life. In its perfect banality, walking became a fitting tool for these artists’ anti-art activities, ironically initiating walking as a form of art [4].

By associating the birth of walking art with dada anti-art practices, Sullivan casts the walk as a non-art, readymade experience mobilized as a tool to revolutionize the role of art in life. In this sense, we might see the art world’s acceptance of walking in parallel with its (hesitant) acceptance of Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Bottle Rack in 1914.

Marcel Duchamp, Bottle Rack, 1914/59 (signed 1960). COURTESY ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

Duchamp’s store-bought rack, presented as a sculpture even though the artist played no role in its production, underscored the autonomy of the artist’s intention and ultimately paved the way for purely conceptual art. Thus, with Duchamp’s readymade, the field of sculpture expanded to include new materials, methods, and collaborations that divorced the production of art from its conception.

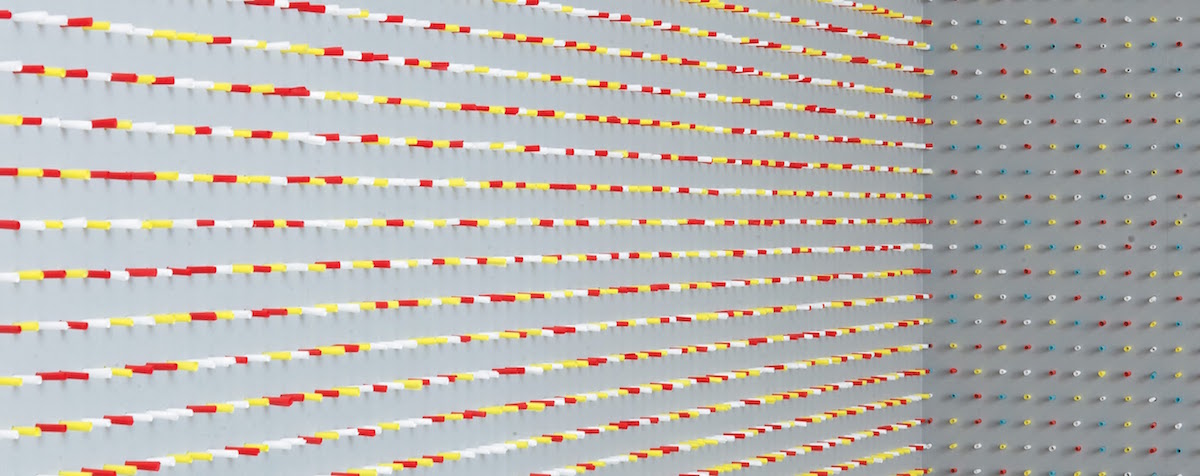

Fifty years later, just as Fulton stopped attending the Royal Academy of Art, Sol LeWitt’s seminal series “Sentences and Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” was published in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Conceptual Art. In it, he revives Duchamp’s distinction between ideas and objects to assert a hierarchy that prioritizes concept and process over material form: “Anything that calls attention to and interests the viewer in its physicality is a deterrent to our understanding of the idea … The conceptual artist would want to ameliorate this emphasis on materiality as much as possible” [5]. This disembodiment of art is literalized in LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #38 from 1970.

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #38, 1969, courtesy of MassMOCA.

The work reads as follows: “Tissue paper cut into 1½-inch (4 cm) squares and inserted into holes in the gray pegboard walls. All holes in the walls are filled randomly” [6]. These instructions, left for someone else to follow, are the work; however the piece is not completed until someone other than LeWitt carries them out. In this sense, LeWitt’s work draws a connection between conceptual art and viewer participation. He seems to assert that an idea as art is an idea that activates a viewer’s reaction.

Though it is unknown if Fulton read LeWitt’s treatise, it is obvious that his work benefitted from such discourse on conceptual art. While less literal than LeWitt’s wall drawings, Fulton’s exhibitions also require viewer participation. Gallery viewers are confronted with a barrage of dates, places, snapshots, elevation diagrams, and poetic verse.

Hamish Fulton: Walk, installation view at Turner Contemporary Photo David Grandorge.

The graphic forms and patterns and Fulton’s precise use of language evoke the rhythm, duration, and compounding emotional texture of a long walk, inviting viewers to step into the role of the walker. Of course there are many elements of the walk that Fulton can’t or won’t translate, but the gaps are filled through an innate understanding of walking. In this sense, viewers are invited to imagine the journey as their own. Thus, Fulton’s formal artworks are not purely optical but temporal and theatrically embodied.

This participatory element of conceptual art, which valorizes the artist’s intention while relying on the viewer to complete the work, opened up a space for what gallery director Claire Doherty calls “situation-specific” artworks [7]. Like LeWitt’s wall drawings, these experiential works elevate process over form. They are not autonomous objects but constructed contexts that others must activate. They produce intentional reactions to place. However, this situation specificity that flourished in the wake of conceptual art was not embraced by many of Fulton’s peers. In particular, the group of artists associated with the land art movement spurned the idea of an ephemeral, interactive art. In a 1968 interview, Robert Smithson, a leader of the group, stated: “I am interested in having the work of art last; the site itself will pass away, eventually erode and enter into passing time, but the work of art more or less has to exclude any kind of time, any kind of participation” [8]. Artists like Smithson were interested in permanence on a geological scale, and thus a human audience was by no means necessary for the work to be complete. Smithson’s Spiral Jetty of 1970.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970. © Holt-Smithson Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York. Photo: George Steinmetz.

embodies this sentiment. Located in the salt flats near Salt Lake City, Utah, this monumental structure, at times under water and at times completely dry, is altered by its environment, yet it remains intact. Its durability through changing conditions is a precondition of its success. The fact that the entirety of the work can only be seen from high above has been interpreted as evidence of an engagement with conceptual art: visitors to must walk out on the jetty, experience the whole thing, in order to construct an image of the whole work in their mind’s eye. However, based on Smithson’s comment, it seems more likely that it was not even made for human viewers. While Fulton has at times been associated with Smithson and the other land artists due to his shared interest in experiential encounters with natural landscapes, this emphasis on permanence runs counter to his devout “leave no trace” philosophy. This tense association between Fulton’s walks and the land art monuments serves as a useful counterpoint in tracing Fulton’s career. Like the land artists, he benefitted from conceptual art in its glorification of intention and the de-emphasizing of the visible object. However, unlike that land artists, Fulton’s work is not simply site-specific, but situation-specific as well.

To summarize, as the conception of art and the production of objects became more loosely related, and as dada happenings gave way to an interest in situation specific art, walking as an embodied and performative act became a possibility that Fulton embraced. With this general overview of the context of Fulton’s career as a walking artist, I now turn to our case studies, which will illustrate how this Fulton’s hybrid identity as a contemplative and cynical walker flourished in this intellectual environment.

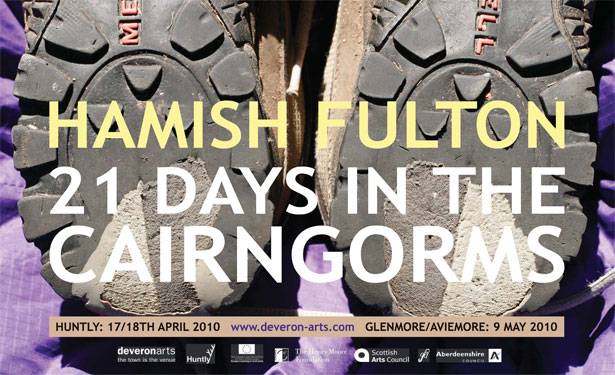

III. In 2010, Hamish Fulton was commissioned to plan a series of walks to be featured as part of the first Walking Festival in Huntly Scotland.

Poster for “Hamish Fulton: 21 Days in the Cairngorms” organized as part of the 2010 Walking Festival in Huntly Scotland.

Image courtesy of Deveron Projects.

The festival was organized by the Huntly Development Trust, the Huntly Tourism Action Group, and Deveron Projects, a local public art initiative acclaimed for “taking the art out of the gallery and making the town that venue” [9]. Their goal was to “encourage more local residents to enjoy the glories of their local landscape and to raise the profile of the town as an ideal base for walking holidays” [10]. Hamish Fulton was the star of the show.

Fulton participated in a series of discussions and planned three walks for the festival: the first two happened in town: a two-hour walk around a single city block in Huntly and a slow walk of three meters over the course of one hour. These invited participants to explore the flexible and subjective nature of walking. For his final walk, Fulton planned to hike the 50+ miles from Huntly’s town square to the Cairngorm National Park by an uncharted footpath through pristinely untamed wilderness.

Though the walks seem simple enough, they had lasting ramifications for the small market town. The through hike established a new popular walking route from Huntly into the mountains. But perhaps the greater achievement was that Fulton inspired Deveron Projects to continue supporting experimental walking projects. By 2013, they had officially incorporated The Walking Institute as a “a walking appreciation programme for and with people from all walks of life” [11]. They explicitly link the development of this initiative to their collaboration with Fulton, stating that his project “formed a starting point of discussion about the many different forms and interests in the act of walking” [12]. In this sense, Fulton’s 2010 Cairngorm walk is a walk that keeps on walking. His pilgrimage to a special destination was not simply a walk, but a voyage to bring something of value back to the community, namely a new route and new appreciation for the regional landscape.

This walk is not often translated into formal artwork, however, it is mentioned in the 2012 artist book Walking in Relation to Everything.

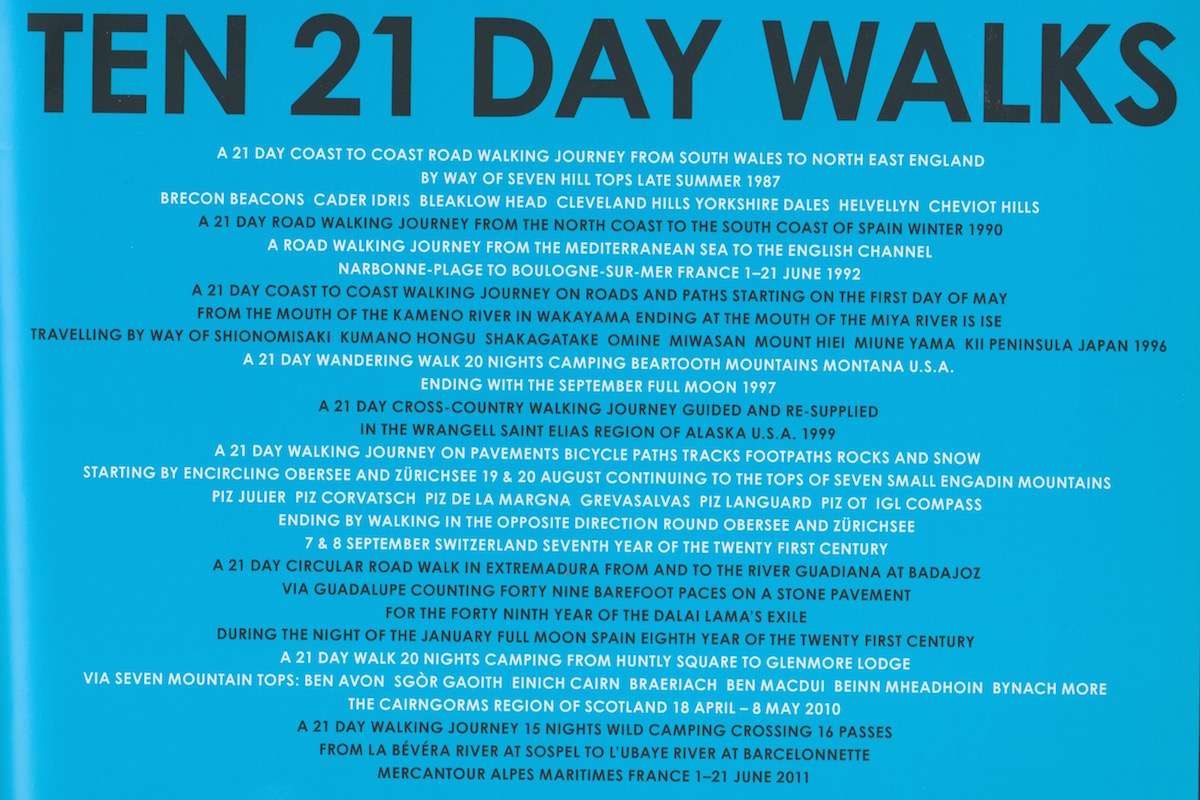

Hamish Fulton, Ten 21 Day Walks, in Walking in Relation to Everying, 2012. Courtesy of Turner Contemporary.

Here, it is highlighted only as part of a series of ten 21 day walks occurring in different locations over the course of 15 years. Of this series of three-week walks, Fulton says:

Dates and numbers are both relevant, important, interesting and conversely—Useless information. (For me) my walk dates and numbers are not part of data overload, they are part of the structure of all my art since 1967. The more I experience and produce the greater the interconnections in the context of current history—simultaneous events [13].

Thus, this walk is cast as an engagement with current history, an attempt to relate to “simultaneous events. In this sense, Fulton’s Cairngorm walk can be seen as culturally productive, the activity of a contemplative walker. Fulton acts as a fully endowed member of society, a maker of social situations, and a catalyst for cultural change.

IV. Prior to his collaboration with the town of Huntly, Fulton engaged in a very different kind of project. As he describes it:

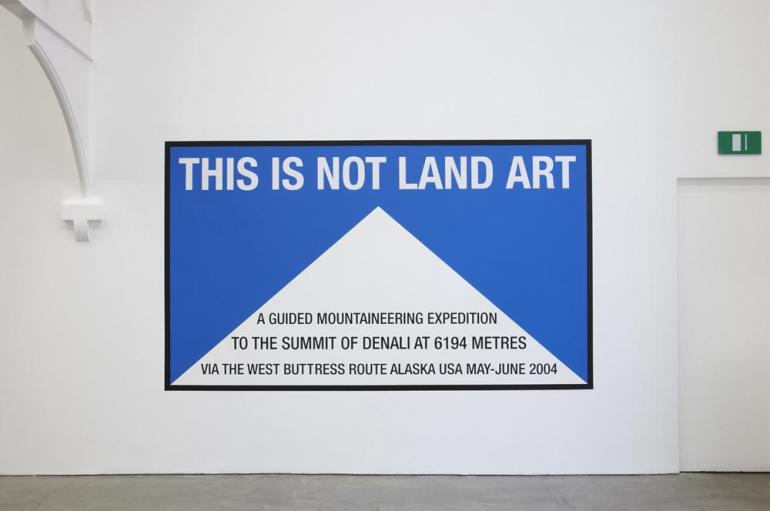

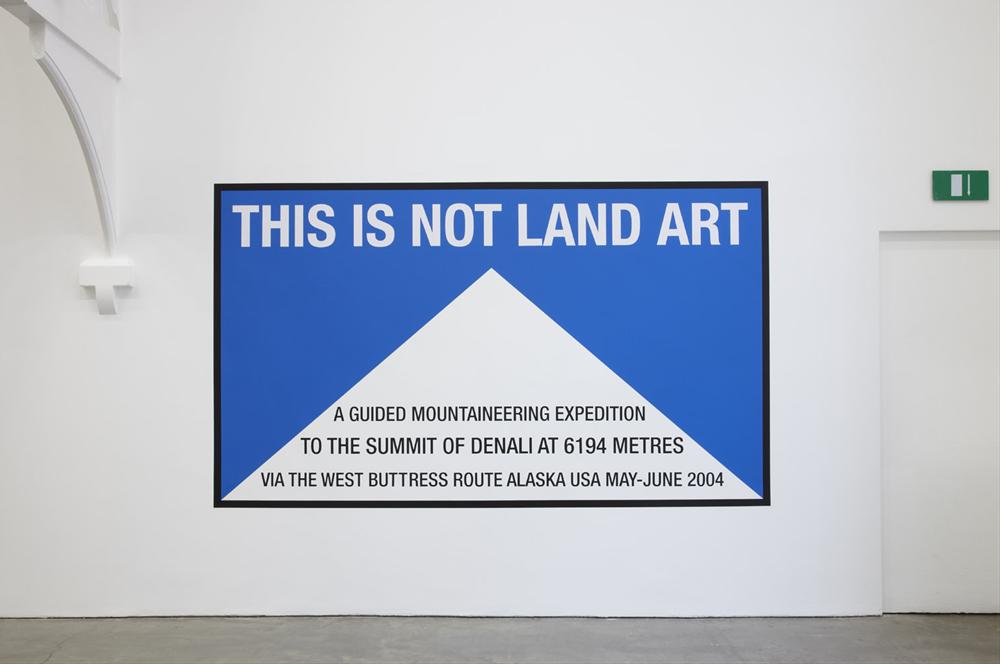

In 2004 I had the idea to make a comment on US land art. I saw a gap in art history—no land artist had summited the highest mountain in North America. … land artists had no interest in summiting Denali, but I, not a land artist, did [14].

In this sense, Fulton’s walk to the peak of Denali is a pointed critique, an overt gesture to distance himself from his peers.

Hamish Fulton, This is Not Land Art, installation view, Ikon 2012 Photo: Stuart Whipps.

This clear opposition to land art is particularly interesting because these were his peers. His classmate and long-time walking partner Richard Long was a leader in the European iteration of this movement, and Fulton has admitted that during his first trip to the US after leaving art school, he “thought about making land art” [15]. However, he was soon disenchanted by the movement’s lack of humility in the face of nature. His comment on land art posits an alternative: nature, not man, is a sculptor. While land artists sculpted forms for an omniscient viewer outside of time, Fulton saw the earth itself as the creator while he simply created the temporal conditions for an utterly human viewing of its forms.

It is interesting to note that both Fulton and the land artists regularly invoke indigenous peoples’ achievements as a model. However, unlike Smithson and others who praised the monumental Aztec and Mayan temples, Fulton idolizes figures of resistance like the Sioux chief Sitting Bull. In fact, on his first trip to the US in 1969, his goal was to retrace Sitting Bull’s steps in his battle against the US government in the late 19th century. In this sense, we might consider Fulton’s ideology aligning with an idealized notion of the relationship between indigenous people and the land, a nostalgia for a pre-settlement way of life more in touch with natural rhythms. Unlike the temples, Sitting Bull’s actions were temporary, short-lived, but they activated a situational reaction that continues to have ramifications. While Fulton’s ideals could be problematized as an invocation of a noble savage stereotype, they nonetheless offer insight into the terms and conditions of his difference from his land art peers. While his contemporaries sought to make their mark on the land, Fulton sought to make a ripple across a stream—a blip in a fluid environment.

Thus, we may consider Fulton’s Denali walk as a cynical walk. Rather than engaging with society, he rejects his peers and walks in order to distance himself from their glorification of stability. In this sense, he is an escape artist, using his creative practice to avoid the pitfalls of ego that he saw as a driving force in contemporary sculpture. But this escape is not for its own sake; there is a suggestion that through this escape Fulton has access to privileged knowledge that not only divides him from his peers, but gives him the upper hand. Thus, he is an experience seeker. he walks in search of elemental truth outside of society’s obstructions.

V. This analysis has looked at Fulton’s walking practice as a product of conceptual and situational art that is built upon a constitutive opposition to sculpture and land art. This art historical perspective illuminates the conditions that allowed walking in general to flourish as a creative practice. As we have seen Fulton seized this opportunity to pose the idea of a walking life and a walking culture. What could life be like if we ceased being settled and took off on foot? In answering these questions, Fulton has had to negotiate his ideological nomadism with his identity as a culturally engaged producer. Fulton’s practice embodies the tension between the nomad and the pilgrim. Fulton is at once a pilgrim, whose trips are always predicated by a return to society, ideally bearing intellectual gifts. Yet he is also a nomad, a cynic, capable of ridiculing society because he is separate from it, living a subversively mobile life. As an embodiment of these conflicting modes of travel, what can Fulton teach us about secular pilgrimage and modern nomadism more broadly?

[1]. Frédéric Gros, A Philosophy of Walking, translated by John Howe (New York and London: Verson Press, 2014), 1-23.

2. Lexi Lee Sulivan, “Stepping Out”, in Walking Sculpture: 1967-2015 (Lincoln MA: de Cordova Sculpture Park and Museum, 2015) 18.

3. Sullivan, 19.

4. Sullivan, 15.

5. Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” in Harrison and Wood edit Art in Theory

6. “Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing #38” on the MassMOCA Website: https://massmoca.org/event/walldrawing38/ (Accessed May 31, 2018)

7. Claire Doherty, Situation, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009) 2.

8. Robert Smithson, Irving Sandler and Alexander Nagel, “An Interview,” in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics No. 63/64, Wet/Dry (spring/autumn 2013) 289.

9. Deveron Projects, Walking Festival Press Release, Deveron Projects: Huntly, Scotland, 2010) 1.

10. Deveron Projects, Walking Festival Press Release, Deveron Projects: Huntly, Scotland, 2010) 1.

11. Deveron Projects, Walking Institute Vision Statement, Deveron Projects: Huntly, Scotland, 2010) 3.

12. Deveron Projects, Walking Institute Vision Statement, Deveron Projects: Huntly, Scotland, 2010) 3.

13. Hamish Fulton, Walking in relation to everything, (London: Turner Contemporary, 2012) 46.

14. Hamish Fulton, Walking in relation to everything, (London: Turner Contemporary, 2012) 28.

15. Ben Tufnell and Louise Hayward, “Chronology,” in Walking Journey (London: Tate Publishing, 2002) 113.

***

Casey Curry is a graduate student studying the History of Art at the University of Oregon. Her research focuses on contemporary artists and their role in global pilgrimage landscapes. Previously, Curry worked as an art educator and curator in Boston and recently had her work published on Big, Red, and Shiny.