Introduction:

This text will examine walking as a means to experience and consider uneven geographical development, making the claim that current processes of globalisation can be grasped through an in-depth examination of a single stretch of coastline. We also introduce walking as an aesthetic approach for producing situated knowledge that is partisan with communities affected by these processes. Walking can be an ethos of engagement with the world that is attentive to the politics of everyday life; a practice of orientation capable of bringing seemingly abstract global problems down to the scale of people’s lives.

Walking route alongside airport toll road

Over 11 days and nights in February of this year (2018), we walked across the 42 km of Jakarta's historically neglected and currently much contested northern coastline. During our walk, we stayed in a fishing community currently facing eviction and subject to flooding from the airport dam just upstream and from rising sea-levels, a Ruko (a 4-storey integrated shophouse typically associated with Indonesia’s Chinese-Indonesian population), a kampung controversially evicted two years ago, an Air-BnB on the 30th floor of a luxury housing block above a mall (the sort of development responsible for the flooding), an artificial beach in a faded Suharto-era theme park, a passenger ferry terminal, and a vast housing block outside of Jakarta where waterside communities have recently been evicted to. The housing block is intended to become the largest in South-East Asia.

Our walk from kampung Dadap, a small fishing community just west of the administrative boundaries of Jakarta, to the housing estates of Marunda, on the easternmost border of the administrative boundaries, crossed areas and neighbourhoods of prolonged urban disinvestment, and, conversely, new areas of speculative and risky hyper-investment. The walk was the first step in an ongoing endeavour to, as artists, come to terms with and intervene in the massive spatial, social, and ecological changes currently taking place in North Jakarta.

Map of route walked

These changes are notably occurring through the Jakarta government’s proposed Great Garuda Sea Wall project (GGSW). The GGSW is a 32 kilometre seawall designed to enclose Jakarta Bay and solve Jakarta’s intractable flooding problems. The plan will ‘Dubai-ify’ Jakarta’s coastline, including a huge waterfront city on a series of man-made islands to be built in the shape of the garuda, Indonesia’s national symbol. This megaproject is laden with symbols, both those drawn from the nation’s past, and those taken from circulating images of ‘global cities’ such as Singapore, New York, and Hong Kong to embrace an imagined prosperous future within globalisation. Aesthetics are used in conspicuous ways to promote the project as a compelling vision of the future. The wishful images of developers and the urban bourgeoisie are ever-present on urban billboards, and represented in architectural simulations, renderings, models and advertisements.

Designs of the Great Garuda Sea Wall

Waterfront city, and a roadside billboard for ‘world class’ superblock

We use walking as a non-spectacular counterpoint to this regime of images, and as part of a broader repertoire of artistic methodologies to “mount[...] a claim for the coast as a living present, rather than as a frontier to be exploited by nationalism and globalism of the past and future perfect”[1].

In contradistinction to the ambitions of early Land artists who employed walking as an aesthetic practice, we cannot imagine the landscape in which we walked as an ‘open field’. This better describes the creative techniques of developers. Aestheticised renderings of the ‘world-class’ city to come depict North Jakarta coastal areas as a sort of de-historicised ‘no-man’s land’ awaiting development. Political elites and the bourgeoisie have long hailed private developers for turning what was formerly swampland into spaces of cosmopolitan capitalism. In truth, North Jakarta has long nurtured ‘subaltern cosmopolitanisms’, and communities there have contributed in important ways to Jakarta’s contemporary identity. For us, walking has the potential to narrate a vision of urban society that is partial, partisan and accountable to the lives of the people we walk amongst and attentive to the sedimented historical geographies that inform the present. Far from an open field, our walk took place within a tightly packed and constrained social-cultural field.

View of fisher settlement

As developments progress, the lives of the urban wealthy and the urban poor grow closer at the same time as they grow more sharply distant. An archipelago city perhaps fitting for an archipelagic nation. We offer the following field notes in order to give an impression of the passionate and banal geographies of North Jakarta’s contested present:

Field Notes:

On the first night of our walk, a military convoy enters the fishing community of Kampung Dadap where we are staying. The convoy is escorting heavy machinery through the neighbourhood’s solitary access road leading to the seaside that makes up the neighbourhood’s northern boundary. Their aim is to escort the heavy machinery to a cleared plot of land where houses had recently stood, and deposit the machinery so that work could start on a housing block where residents would be relocated. On this occasion, the military and machinery arrived at 11 pm. On subsequent occasions, they have arrived at 3 am. On each occasion they have been prevented from entering by residents who have blockaded the street, called to attention by the tin drum (a cooking pot and wooden spoon) of a vigilant resident.

Later that night, rain begins to fall. It continued for a good portion of the night, and when we wake the next morning, much of the kampung is knee to waist-deep underwater. As usually occurs after heavy rainfall, the gates to the dam of the Soekarno-Hatta airport just a few kilometres to the south are opened so that the airport can operate unimpeded. We spend much of the day wading through the waters, meeting the women who can continue to work shelling muscles on mounds raised above the surrounding areas. These mounds form a tangible basis for residents’ claim of a right to live in the area, as they themselves have literally made the land their houses are built on with the persistent everyday labour of retrieving muscles from the sea and shelling them. We then take a boat out of the mouth of the canal to inspect the artificial island lurking between Kampung Dadap and the open ocean - island C out of a planned 17 spanning from A to L. Rain is still falling and the air is misty, but the island can be seen nearby. The small boat struggles to re-enter the estuary and reach the bamboo docks where the fishing boats are moored.

The following night we walk a narrow, busy and dusty industrial road plied by trucks and angkots (public transport vans that typically service poor areas and poor residents). There is no pavement, and we sway between the gutter and the road as we make our way east, stopping at brightly lit Indomarts to drink. The area is gritty, and the people working there have a rough and crass worker’s quality to them. Finally, we reached the turn-off to the area that will provide our second night’s accommodation; the corporate-built development of Pantai Indah Kapuk 1. Unless we walk several kilometres further east, our only way of entering the area on foot is to illegally take the overpass of a toll road, passing over another toll-road that takes vehicles from the Soekarno-Hatta airport to central Jakarta. Car headlights cut a swathe of modernity between industrial estates and mangrove swamps. Down the other side of the overpass is Pantai Indah Kapuk 1; glass tower blocks, 40-foot wide gleaming advertisements (primarily for Pik 2; another satellite city to be built by the same developers), neat curbs, trimmed grass, hedges and municipal palms.

Kampung Dadap and Pantai Indah Kapuk 1 are ‘distant proximities’; about 4 kilometres apart as the crow flies; but, as the toll road from the airport bypasses Kampung Dadap, at least 8 kilometres by car, and 12 kilometres for most other forms of traffic. There are ‘parallel mobilities’; on subsequent trips to the north, we have walked a concrete retaining wall used by kampung fishermen, chicken farmers, and rubbish pickers that narrowly separates a mangrove swamp from the toll road.

Following the partially built toll road from Kampung Dadap to Pik 1.

In Pantai Indah Kapuk we stay in a design studio on the top floor of a shophouse (ruko) owned by a Chinese-Indonesian friend of Irwan’s, Yeni. Exploring the ruko-lined boulevards of Pantai Indah Kapuk, Yeni points out the numerous elite brothels located there thinly disguised as spa and health clubs with names such as Blow Art, Boobles, Foxy Spa, Desensual Massage, Golden Hands, and Sky Sensation. Descending the stairs in the morning, we enter a hip cafe with minimalist concrete decor, delicate patisseries and lattes. There we breakfast. Creamy mushroom pasta with parmesan. Leaving our bags behind, we walk the newly-built bridge connecting Pantai Indah Kapuk 1 with Golf Island (island D of the proposed 17). A security guard tells us we can’t pass, but, when we point out the families and couples who had been permitted to pass and are now taking selfies on the bridge, he reluctantly lets us through. Two long rows of shophouses have already been constructed, and work is continuing apace on housing to the west and east of the shophouses. Built without permits, the buildings register elite informality as a constituent part of world-class city making. The sound of concrete pylons being driven into the ground so that the island doesn’t dissolve away, tak tak tak. Mangrove trees have already begun to take root and grow amongst boulders in the shallow waters on the southern side of the island. Waterbirds, stalks and herons.

Mangroves to the west of Pik 1

The Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute:

To elaborate on walking as a methodology for making global processes and complexities sensible and experienceable on a personal level, we will consider a notable effort to produce ‘emancipatory geographies’ that employed walking as a tactic; the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute (DGEI). Founded by Bill Bunge, a white, male, middle-class professional geographer and Gwendolyn Warren, a young black, female community organiser, the DGEI self-consciously sought to upturn the colonialist and extractive notion of the ‘expedition’. Instead, the DGEI aimed to be a ‘contributive’ expedition and institute that produced ‘situated knowledge through exploration’[2].

In the wake of the Detroit riots, the DGEI explored a one-square mile neighbourhood of Detroit from 1968 and 1972. Through exploration at the level of the neighbourhood, the DGEI tried to bring complex global problems down to earth, to the scale of people’s lives. “The point of these expeditions,” writes Cindi Katz, “was that people should explore their home terrains in order to reclaim and restore them”[3]. Katz offers a concise summary of the DGEI’s activities:

Explorers established a “base camp” in the community where they worked, and lived there throughout the duration of the expeditions... The explorers worked in teams to research issues such as children’s survival and open space, traffic, highrise construction; hidden spaces and cultural expression; rats and garbage; and ‘urban nationalism’. The overarching structure was an analysis of the spaces of nature, mankind, and machines at five scales, the neighbourhood, the metropolis, the nation, the continent, and the planet[4].

The DGEI claimed that the entire history of the U.S.A. could be experienced and understood through a detailed examination of any one-mile tract of its surface. The geographical proximity of spaces of investment and spaces of disinvestment was also studied. Bill Bunge claimed that ‘the seven mile journey from rich suburban Detroit to its poor inner city is a trip half-way around the world in terms of infant mortality rates’. It is this outlook on the possibilities for collectively producing conceptualisations of the world through localised exploration that most interest us in the work of the DGEI.

Conclusion: Orientation

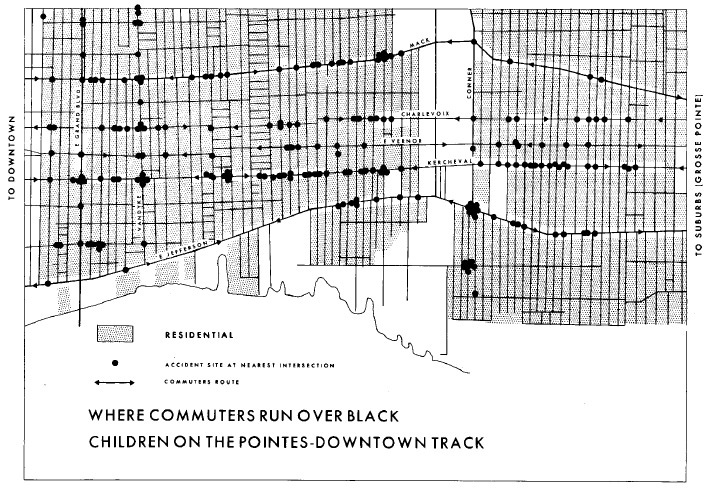

The DGEI’s efforts to conceptualise global problems from the scale of people’s everyday neighbourhoods and ecologies brought together the dust and heat of everyday sense perception with an imaginative sense of the broader structure of social relations that conditioned that sensate life. This practice of orientation sought to coordinate a collective politics by producing maps with such stark titles as ‘Where Commuter Run Over Black Children on the Pointes-Downtown Track’.

DGEI map

This collective practice of orientation was not only enunciated through ‘readings’ of space, but also through embodied practices; participants in the DGEI understood what was ‘geographically out of whack’ by ‘getting a feel of the region. By talking, listening, arguing, befriending, and by making enemies of the humans in the region’[5]. Getting a feel for a region by walking, talking, listening, arguing, allows ‘outsiders’ such as us as artists, or the geographers associated with the DGEI, to orient themselves to emerging socio-political terrain and dynamic geographical landscapes. Walking provides not only potentially productive social encounters, but also an affective experience of separate ecology sets. For example, those of the fishermen who infiltrate remaining mangrove swamps on the peripheries of gated communities unperturbed by the levels of rubbish and pollution to be found there.

Walking, talking, listening, arguing, can plot the beginnings of a sensitive relationship with areas of uneven development such as racialised, gendered 1960s - 1970s Detroit and economically segregated North Jakarta. To be truly partisan in such visceral socio-political contexts, however, requires a commitment to a much longer process of developing affinity, and affinity can only be developed by coming to comprehend people’s singular attachments to their lives and circumstances. What do people defend when they defend their ways of life? How would they like the future to unfold from the present? Practices of collective social, political and geographical orientation, of which walking is one, must take off from such learned affinities.

Author Bio:

We are two Australian artists and geographers, Jorgen Doyle and Hannah Ekin, and two Indonesian artists, Irwan Ahmett and Tita Salina. In February of this year, we walked across Jakarta’s northern coastal region over 11 days and nights in an aim to produce situated knowledge through exploration.

References:

1. Katz, Cindy 1996: ‘The Expeditions Of Conjurers: Ethnography, Power and Pretense’. In ed Wolfe, Diane 1996: Feminist Dilemmas in Fieldwork. Westview Press .

2. Kusno, Abidin 2013: After The New Order, Space, Place and Politics in Jakarta. University of Hawaii Press.

3. Merrifield, Andy 1995: ‘Situated Knowledge Through Exploration: Reflections On Bunge’s Geographical Expeditions’. Antipode 21(1): pp 49 - 70

[1] Kusno, Abidin 2013: After The New Order, Space, Place and Politics in Jakarta. University of Hawaii Press.

[2] Merrifield, Andy 1995: ‘Situated Knowledge Through Exploration: Reflections On Bunge’s Geographical Expeditions’. Antipode 21(1): pp 49 - 70

[3] Katz, Cindy 1996: ‘The Expeditions Of Conjurers: Ethnography, Power and Pretense’. In ed Wolfe, Diane 1996: Feminist Dilemmas in Fieldwork. Westview Press

[4] Merrifield, Andy 1995: ‘Situated Knowledge Through Exploration: Reflections On Bunge’s Geographical Expeditions’. Antipode 21(1): pp 49 - 70

[5] Cited in Merrifield, Andy 1995: ‘Situated Knowledge Through Exploration: Reflections On Bunge’s Geographical Expeditions’. Antipode 21(1): pp 49 - 70