Honorata Martin, Going out into Poland (2013). Image courtesy of the artist.

Within the contemporary condition defined by technological progress, “the simple act of walking” has become “almost obsolete” activity.[i] The subversive character of walking relates to the isolation and alienation of the individual in modernism, as well as questioning “the position of the body itself” by postmodern theory.[ii] Regardless of those premises, people do remain walking as it allows us to create a relationship with both landscape and society. Walking is one of the basic human activities, therefore it remains ferociously human.

Walking as an activity is interlinked with the few questions relating to “why”, “where” and “when”.[iii] According to psychogeography the very idea of a ‘walk’ is constituted through conscious contemplation of both place and walker’s relationship with it. As indicates Tina Richardson in the introduction of “Walking Inside Out”:

“The walker connects with the terrain in a way that sets her- or himself up as a critic of the space under observation, but at the same time, they unite with it through the sensorial acknowledgement of its omnipresence. The space becomes momentarily transformed through this relationship. The psychogeographer recognizes that they are part of this process, and it is their presence that enable this recognition to occur.”[iv]

The actions of psychogeographer as presented above aim at the sensorial recognition of topologies and socio-cultural environments which surround the walker in a given momentum. Simultaneously, the walker is able to recognize her thoughts, emotions, and observations arose as a result of the confrontation with space and its elements.

The notion of psychogeography is a rather volatile one, but its customary assessment allows us to perceive it as a “work in process” which engages subjectively and objectively with the landscape while emphasising emotional and political links to “what is perceived as a capitalist space”.[v] Psychogeography grew out of Situationist International (SI) and is identified as a fundamentally urban phenomenon. This urban character was mediated through the influence of Marxist and Frankfurt School concepts including alienation, culture industry and commodity fetishism.[vi] For Guy Debord, seconded by others such as Asger Jorn “psychogeography” was an attempt to create the renewed urban space[vii] through the "study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behaviour of individuals."[viii] Instantaneously, psychogeography constituted a certain form of a renewed critique that supposed to challenge alienation of the individual.[ix] Regardless of those premises, the praxis of Debord’s psychogeography was unsuccessful to create specific algorithms or fulfil its idealistic objectives, which included the transformation of the modern urban space.

The key figures related to SI, such as Guy Debord or Peter Ackroyd engaged with large urban environments (Paris and London respectively), remaining rather disdainful about the rural landscape. Perhaps, the motivation behind connecting such construct solely with urban space lies in the modern notion that capitalism and social performativity are more urban than rural.[x] However, the definition coined by Debord depicts psychogeography as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals."[xi] Considering this perspective, one cannot fail to notice that the countryside is established as a geographical, build environment[xii] both socially and culturally. Those premises allow for various explorations regarding one’s relation to the space considered as a political construct. Albeit during the last few decades psychogeography has undergone a process of renewal through various radical and subversive practices, countryside remains mostly ignored in a field of psychogeographic explorations. Moreover, its image is often still romanticised or perceived as a place of leisure which allows escaping from capitalist space of a city.[xiii]

Considering this rather deterministic nature of psychogeography the question remains: is it possible to transpose psychogeographic methods and process of dérive into a rural landscape? Dérive is the term interlinked directly with a Debord’s notion of psychogeography. It refers to a walking journey during which one or more persons for a certain period of time drop their activities and relations allowing themselves to enjoy attractions and encounters provided by the landscape.[xiv] The true drift is instinctual, shaped by uncertainty and randomness prescribed by the lack of direction. The certain subverted idea of rural psychogeography can be observed in Honorata Martin’s work Going out into Poland[xv] (2013). The artwork is a specific type of emotional journal from the two-months-long, lonesome journey which, while in process was essentially defined by places and people she encountered. In order to start her walk, Martin dropped not only all of her activities but also as all the things which “defined her social status”[xvi] and position. The only items she took with her were a change of clothes and a sleeping bag. Beginning her walk from her flat in Gdańsk, the artist walked 30 km daily, avoiding big cities. The starting point of the walk were sensations of fear and solitude which pushed the artist to actively engage with space and society. Therefore, at dawn she would knock on random doors, asking locals to host her. The next day she would continue her journey, beginning another dérive. Every time the artist restarted her walk the feeling of anxiety returned since her relationship with the space she needed to leave was already established.

Honorata Martin, Going out into Poland (2013). Video frame. Image courtesy of the artist.

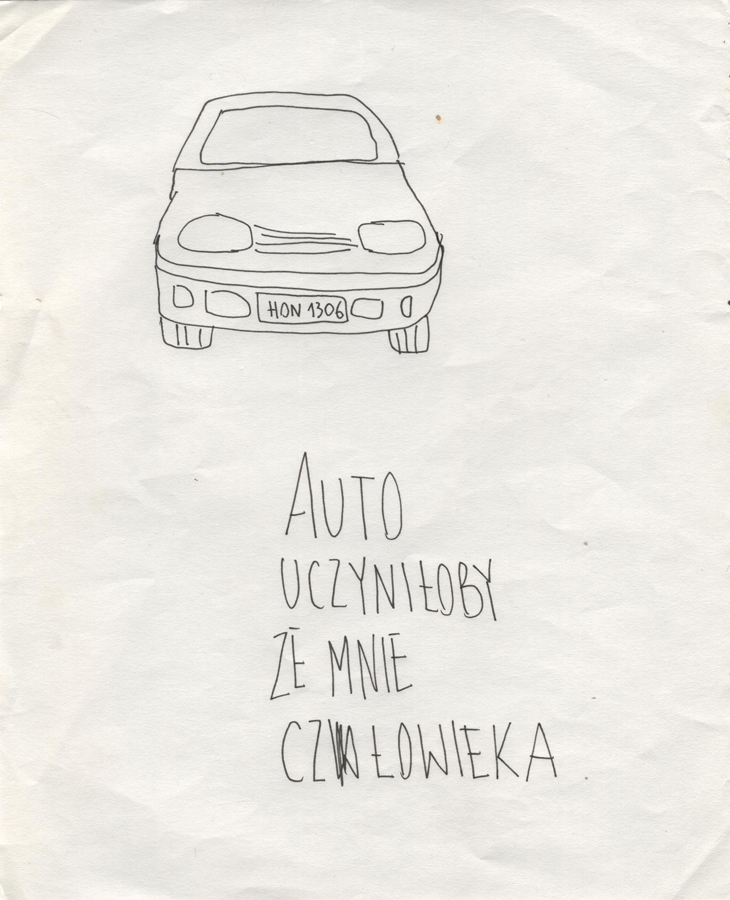

The method used by the artist is personal walking, supplemented by various actions which can be considered as certain genres or: video, photography, drawings or maps. Honorata Martin’s drift was shaped by the randomness of space and encounters; the more absurd or paradoxical were those situations, the more they were likely to transform the process, direction and emotions. This practice allowed connecting standpoints related to artistic, social, geographical and cultural contexts. Created by the artist videos allow us to follow her emotional experience marked frequently by strong sensations of fear, anxiety, and loneliness, while used maps bring the idea of the spatiality of experience. The drawings accompanied with descriptions of situations which Martin experienced, dialogues with people she encountered and her feelings regarding those mark the walking path with emotional highlights, generating stories detached from their spatial and temporal contexts.

The notion of psychogeography can be seen as a tool used by the artist instinctively. Those instincts allowed the artist to treat the walk as a cognitive process - both subjectively and objectively while taking into account social and cultural processes linked with spatial and sensorial experiences. Her investigations were usually focused on the impact of particular geographical and cultural environment on the walker. Through avoiding big urban agglomerations and focusing on small villages and towns she draws the panorama of landscape and society who usually remain unnoticed by urban-focused elites[xvii] and draws a comment upon it. The panorama she creates it’s far from utopia and demonstrates the rather overwhelming vulnerability of the walker. Martin’s practice seems to prove how the basic, human activity of walking was dehumanized and how awkward seems the figure of a lonely female walker for others who often pointed fingers at her while passing in their cars. Therefore, what Martin presents to us is the status of a walker, particularly a female walker in contemporary life.

Honorata Martin was concentrated on the act of experiencing the walk, “facing her own fears and the uncertainty, friendly or hostile meetings of the “stranger” with the “locals” - testing the basic social relations”[xviii]. Certain importance can create the idea of being “the other”, a drifter, a wanderer without any particular goal, an artist whose project remains misinterpreted for those who are directly engaged in it. The work’s emotional charge creates a certain narrative: it relates to everyday anxiety and lonely confrontation with both landscape and local society. The other sources of rather fragmented narratives are derived from the relations she managed to create with others. Therefore, the work can be seen as an investigation of personal, but also shared emotional geographies[xix] of the walked landscape. The focus on social elements creates certain “geographical sensibility” [xx] which implemented directly into everyday social life allows us to see quotidian as artistic and the other way around. Going out into Poland approaches critically, aesthetically and emotionally the practice of walking through the unknown rural landscape. This landscape and local communities enable the artist to recognize her own emotional responses highlighted in the presented work. The narratives – personal and shared guide the walker through the rural landscape allowing her to create a relationship with the space seen as both geographical and cultural construct.

Honorata Martin, Going out into Poland (2013). Drawing ("A car would make a human out of me"). Image courtesy of the artist.

[i] Jacks, Ben. “Reimagining Walking: Four Practices”, in: Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 54, No. 3 (February 2004), p. 5.

[ii] Jacks, Ben. “Reimagining Walking: Four Practices”, in: Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 54, No. 3 (February 2004), p. 5.

[iii] Psarras, Vasileios, Emotive Terrains. Exploring the Emotional geographies of the city through walking as art, senses and embodies technologies. PhD Thesis. Goldsmiths University of London, 2015, p. 14. available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bc00/fc2b3f2b6a70c11ec94b4b327c280d5097c0.pdf

[iv] Richardson, Tina, “Introduction”, Walking Inside Out, 2015, p. 18.

[v] Petts, David. “Archaeology and Psychogeography” (15 December 2011). Available at: http://outlandish-knight.blogspot.com/2011/12/archaeology-and-psychogeography.html.

[vi] Elias, Amy J. „Psychogeography, Détournement, Cyberspace”. In: New Literary History, Vol. 41. No. 4. “What is an Avant-garde?” (Autumn 2010), p. 821.

[vii] Elias, Amy J. „Psychogeography, Détournement, Cyberspace”. In: New Literary History, Vol. 41. No. 4. “What is an Avant-garde?” (Autumn 2010), p. 821.

[viii] Debord, Guy-Ernest, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” (1955), available at: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/2

[ix] Elias, Amy J. „Psychogeography, Détournement, Cyberspace”. In: New Literary History, Vol. 41. No. 4. “What is an Avant-garde?” (Autumn 2010), p. 821.

[x] Petts, David. “Archaeology and Psychogeography” (15 December 2011). Available at: http://outlandish-knight.blogspot.com/2011/12/archaeology-and-psychogeography.html.

[xi] Debord, Guy-Ernest, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” (1955), available at: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/2

[xii] Considerations about rural psychogeography can be found in Write The Map post: ”Mapping Inside Out – Psychogeography, Psyche & Personal Narratives”. Available at: https://writethemap.wordpress.com/2017/08/13/mapping-inside-out-psychogeography-psyche-personal-narratives/

[xiii] Write The Map post: ”Mapping Inside Out – Psychogeography, Psyche & Personal Narratives”. Available at: https://writethemap.wordpress.com/2017/08/13/mapping-inside-out-psychogeography-psyche-personal-narratives/

[xiv] Debord, Guy-Ernest, “Theory of the Dérive” (1958), available at: http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/2.derive.htm

[xv] Honorata Martin’s video and some images of the work can be seen at: https://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/martin-honorata-o-wyjsciu-w-polske

[xvi] “Filmoteka Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej” Available at: https://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/martin-honorata-o-wyjsciu-w-polske

[xvii] The promotional material of the exhibition “Society is mean” Raster Gallery, Warsaw (2014). Available at: http://en.rastergallery.com/wystawy/cipedrapskuad-honorata-martin-dorota-maslowska-maria-tobola-spoleczenstwo-jest-niemile/

[xviii] Ibidem.

[xix] On emotional geographies one can read in: Anderson, Kay; Smith, Susan J., “Editorial: Emotional Geographies” (2002), available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1475-5661.00002

[xx] I used term “geographical sensibility” after Psarras, Vasileios. Emotive Terrains. Exploring the Emotional geographies of the city through walking as art, senses and embodies technologies. PhD Thesis. Goldsmiths University of London, 2015 available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bc00/fc2b3f2b6a70c11ec94b4b327c280d5097c0.pdf